Evan Morgan, circa 1930s. Poet, eccentric, and crypto-Luciferian infiltrator.

It does not escape the notice of this blogger that the subject of today’s post shares my surname. The subject also happens to have been a horribly iniquitous person. Fortunately, there is no direct kinship, as Evan Morgan begat no children. Also, my own line of Morgans have been split off from the Welsh Morgans for many generations, having been in North America since the late 18th century. We are the descendants of a fisherman named Thomas Rhydian Morgan who, along with his wife, Christina Kent Morgan, left Wales in 1786 and settled in the town of Shelburne in the maritime province of Nova Scotia, Canada. Therefore if I have any consanguinity with this hideous fiend, it is extremely remote. (Ouf!)

Something I was not well aware of until I read the testimony of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua was the surprising degree to which occultists, pagans, and devil-worshippers had infiltrated the Catholic Church. It is often said that Freemasons, communists, and various other enemies of the Church have, for decades, been worming their way into the ranks of the clergy, wreaking their subversion from within. And this is commonly accepted. But when it comes to tales of “Black Masses in the Vatican,” it almost becomes too much: for many Catholics, this is just too bizarre and unbelievable. It comes across like something out of a novel by Father Malachi Martin—and Fr. Martin was a suspicious character himself. His loyalties seemed to be forever shifting; sometimes he was a modernist when it suited him, and other times he was a traditionalist. He contradicted himself on many matters, and much of the time it almost seemed as if he was making things up as he went along. So whenever something carries “a whiff of Fr. Malachi Martin,” one is tempted to dismiss it as outlandish.

Such was my original reaction when I first began reading the transcripts of the Gagne-Bevilacqua interviews. I thought to myself: “purement fantastique. Incroyable!” But once I began researching his claims, to see if certain points might be corroborated, I was surprised to find that much of the people and events he mentioned adhere quite closely to recorded history. In the next post, I will provide a summary of the two weeks he spent in Rome in the summer of 1917. But first I would like to share what my research revealed—particularly as it regards his mention of a certain Evan Morgan: the unsavory and ghoulish person whose last name sends shivers up my spine: to think that he and I might share a common ancestor, somewhere back among the Morgans of Wales ages ago.

Evan Frederic Morgan was the scion of a wealthy family of the English nobility. Like many families of the aristocracy, the Morgans were what might be termed “fashionably eccentric and decadent.” In fact, they took their eccentricity and decadence rather seriously. His mother seemed to believe she was some sort of bird (an actual bird, that is, and nothing to do with the British slang for a good-looking girl). His grandfather, Frederick Courtenay Morgan, stood as a so-called “Conservative” Member of Parliament—and yet he was also a good friend of Richard Monckton Milnes, who owned one of the largest collections of Victorian-era pornography and was a patron of the poet Algernon Swinburne, a man of many perversions who composed much blasphemous anti-Christian verse, including a sneering condemnation of the Catholic Church entitled “Locusta.” Verily, the Morgan family was in the top tier of an English upper class that shewed an outward conservatism but led a secret life of terrible debaucheries.

Evan Morgan himself would continue the trend. As a young man at university, he converted to Roman Catholicism. But his conversion was insincere and superficial. What Morgan liked about the Catholic Church were its regal and extravagant trappings: the sublime atmospherics of the Latin Mass, the lace surplices and gold-tinged chasubles, the Gothic architecture, and the high ceremony of the papal court. What he did not like, however, was the Catholic faith itself. He was an awful despiser of Christ—so much so that he became an avid occultist. At around the same time he converted to Catholicism (the period when he was at Eton College at Oxford), Morgan also joined a Luciferian society known as the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), which is where he met and befriended the then-leader of the O.T.O, Aleister Crowley. Crowley became Morgan’s mentor; Morgan was Crowley’s ace pupil. Crowley deemed him “Adept of Adepts” (referring to a title which, according to my research, seems to be considered a high position in the rankings of ceremonial magicians. I did not research the occult too extensively; a Catholic must be prudent in these matters. The more one investigates the dark side, the more one runs the risk of coming face to face with the abyss).

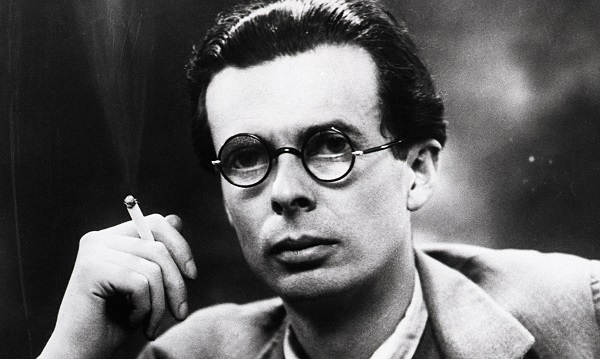

Morgan thus began to lead a double life. On a typical Saturday evening, Morgan and Crowley would meet up in London, to smoke opium and to cruise the city’s squalid homosexual districts (both men were sodomites). Their night would culminate back at Crowley’s lodgings, where they would undertake “mystical” readings of the Kabbalah. Then they would set up an altar, with hexagrams, idols, and candles, and they would try out various unspeakable satanic rituals—first at midnight (“the witching hour”), then later at three o’clock (“the hour of the wolf,” or “the devil’s hour”). The next morning, a tired and bleary-eyed Morgan would show up for Mass at the Brompton Oratory to blasphemously receive Holy Communion. His close association with Crowley lasted between 1912 and 1913. During this time, Morgan informed Crowley that his ultimate goal was to summon a living demon. Together, they never succeeded. Crowley left the country in 1914 for Paris and then the United States. Morgan remained in England: writing bad poetry and keeping up appearances among the London aristocracy (when Aldous Huxley satirized high society in his novel Crome Yellow, he modeled the most immoral character after Evan Morgan). Morgan joined the Welsh Guards when the war broke out, and spent a year and half stationed in France. Most British soldiers were expected to spend three years in service, but Morgan used family connections to weasel out of a long-term obligation.

The young Evan Morgan during World War I, with his father Courtenay Morgan, the 1st Viscount Tredegar. The advantages of privilege: the elder Morgan spent most of the war on his private yacht, which the Royal Navy had converted into a floating hospital. Meanwhile the son served a shortened term in combat.

Upon returning to England from the front, Morgan rekindled his acquaintances in occult circles. On a visit to Glasgow, he began a friendship with a mysterious older woman named Myriam MacKellar, who claimed to be the Jewish wife of a wealthy Scot, and also to be an expert on the Hindu Vedic texts.

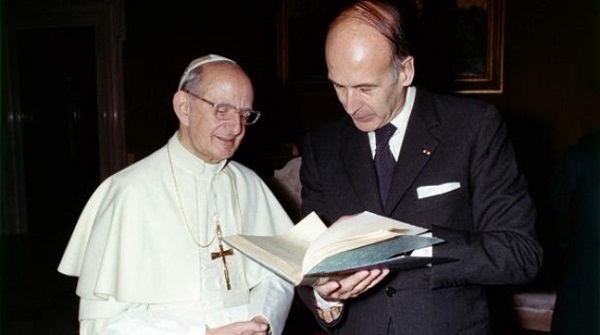

In 1916, Morgan made a pilgrimage to Rome, where he met up with an influential group of British-born clergy in the curia. He presented himself as a connoisseur of the liturgy, and he managed to charm them with his personality, a false display of piety, and a smattering of acquired expertise. Using his family’s wealth and status as leverage, he procured for himself a spot in the Vatican as a papal chamberlain.

It is important to note that no one in Rome was likely aware of his secret life as an occultist. It was 1916. Europe was in the midst of a catastrophic war. The doings of the eccentric members of the English aristocracy would simply not have shown up on the Vatican’s radar. It is also useful to consider that the pope at the time, Pope Benedict XV, was a holy pope and a staunch traditionalist. He was the author of the prophetic encyclical Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, in which he warned of the coming end of civilization—the natural result of Europe forgetting her Catholic roots and embracing the heedless nihilism of modern philosophy. (Miserere nobis; his assessment was correct). Nevertheless, the historical fact remains. This same man who decorated his home with inverted crucifixes and was a known friend of Aleister Crowley, also happened to be an actual Chamberlain of the Sword and Cape in the very court of Pope Benedict XV. Normally we might be able to look on this as nothing other than a tragic accident of history. But in early July of 1917, Evan Morgan traveled to Rome to mark the newly-minted refinements which had been made to the pope’s Prefecture. The Vatican had become a veritable convention of liturgical experts and enthusiasts. Also in Rome at this time were two young seminarians: Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua and Alessandro Falchi. What Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua witnessed there, he described as “the most harrowing event of my entire life. It will haunt me to the grave.”

Evan Morgan (left) with parrot, circa 1920s. Morgan owned a menagerie with many exotic birds, and was a trainer of carrier pigeons during World War II. He came from a family with an avian obsession. His mother, Lady Katherine, reportedly built bird’s nests to human scale at the family estate, Tredegar House, where she would sit in these nests like a hen. Her son’s poetry was rank: “The birds of love with plumage rare / Sped in circles ‘bout my hair.”