During the early stages of my research for this blog, I told Baltasar Fuentes Ramos about the aforementioned episode in Rome in 1923, when poor “Don Battista” was left on the losing side of a geocentrism discussion. Fuentes found that one interesting, because currently, he said, Pope Paul VI holds the opposite view on the subject: nowadays he would agree with Jerome Fitzgerald (were he alive, that is. Fitzgerald, who was described as “middle-aged” in 1923, is almost certainly deceased by now). This got Fuentes to talking about what he knows of the pope’s reading habits and intellectual life, which I was naturally fascinated to hear of. In one of the first entries on this blog, I published what Fuentes told me about the pope’s lifestyle and diet. The following, then, is some of what he has come to know about the pope insofar as his views on doctrine, theology, and ecclesiology.

It is helpful, in understanding the progress of Paul VI’s thought, to appreciate that his worldview can be roughly divided into three distinct phases of his life: there is early, middle, and late Pauline. The first phase dates from 1917 – 1935, where he was neither a liberal modernist nor a stalwart traditionalist; he was essentially a theological moderate. His attitudes were mostly aligned with one of his dearest mentors during this period, Eugenio Pacelli, who would later become Pope Pius XII (regnum: 1939 – 1958). The two became friends during their tenure together at the Vatican Secretariat of State. Much like Pacelli, Montini believed the faith could be reconciled with modern science. He believed that the Church had been mistaken to condemn Galileo, and he believed that the ascendant theory of evolution might somehow be harmonized with sacred scripture. He was cautious on this, of course. He was by no means certain. He would’ve agreed with Pacelli’s delicate approach to evolution in the 1950 encyclical Humani Generis: that theologians and scientists should carefully and thoughtfully search into how evolution could be reconciled with creation, so long as they preserved the doctrine of the first pair, Adam & Eve. Although he did not endorse evolution outright with Humani Generis, Pacelli failed to condemn it. He left it open as a possibility: and this was a lamentable instance of neglect which brought on decades of Catholic unbelief in the true and scriptural account of creation.

The second period of Montini’s thought would be from 1935 – 1972, when he was brought low by a demonic oppression. A recent headline on gloria.tv proclaimed that antipope Benedict XVI’s “head ‘does not work entirely’ anymore”—and sadly, the same thing could be said of Montini during this terrible stretch of nearly four decades. (A brief aside: I have been contacted by some secular readers of this blog who find the subject matter intriguing, but they have told me that some of the terminology is confusing or arcane. It is especially strange, they have told me, to see Francis and Benedict XVI and John Paul II labeled “antipopes” when the whole world knows them as “Pope Francis” or “Pope Benedict.” It is imperative for this blog, however, that these men be considered antipopes. For clarity’s sake, then, I have decided to create a Glossary of Terms that I can link to for words or phrases that might be perplexing for those unfamiliar with traditional Catholicism or the theory of Pope Paul VI’s survival. I will add to it as I make new posts. The first entry is “antipope.” I will also try to go back and create links to it from certain words used in my earlier posts). At any rate, Montini during this time was confined to a mental prison, constantly harassed by demons to an extent where nearly anyone else would probably have gone mad. I briefly sketched out in an earlier post how “an unspeakable goetic malignancy had taken hold of Montini’s soul and oppressed him.” Truly, his head did not work entirely. His outward self was for the most part a charade—he was like a puppet dangling from strings, and he could only but observe the dreadful machinations going on around him; he was impotent to stop them. The only thing he possessed was the awful awareness that his earlier views had been completely wrong-headed. There could be no such thing as sitting on the fence and being a moderate. There could be no compromise between the Church and her enemies, for “what concord hath Christ with Belial?” When he began to emerge from his accursed state, he asserted himself firmly as a traditionalist: when he issued Humanae Vitae in 1968, and when he declared that “the smoke of Satan has entered the Church” in 1972. Fuentes once told me: “when this pope finally comes out of hiding and takes up his chair in Rome, the Church is going to have a pope the likes of which no one has seen since St. Leo the Great. (Pope Leo, of course, is known for his famous standard: “innovate nothing; be content with tradition”).

The third period is his life in exile, from 1972 until the present. While he was being sheltered by a group of Greek Orthodox monks at a Cretan monastery called Godia Odigitria, he spent much of his time in the library there, an eager autodidact, re-educating himself. The scales had long since fallen from his eyes: more than anyone else in the world, he had witnessed first-hand the presence of the enemies of the Church inside the Church: in the Vatican itself, from the lowest priests to the highest prelates, seeking to bring the Church to ruination from within. He knew that the crisis of tradition was older than Vatican II. It was older, even, than the modernism of the early twentieth century. It went as far back as St. Robert Bellarmine, Galileo, and Pope Alexander VII in the sixteenth century, and the attempts of later popes to overturn the condemnation— trying to cozy up to modern science. (“Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do”). Jerome Fitzgerald had been correct: the Church was right about heliocentrism the first time. It was nothing but heresy.

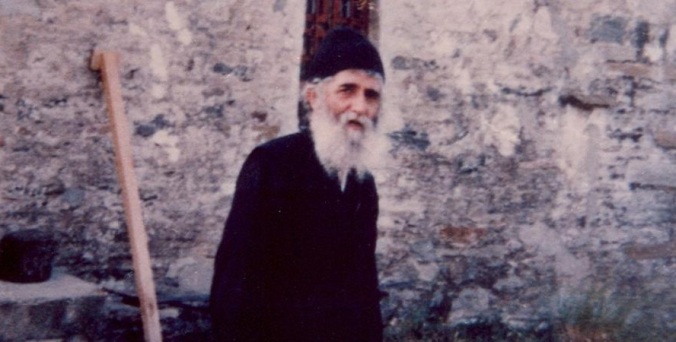

The Godia library offered Pope Paul a wealth of patristic works, and he surveyed the Early Church Fathers on the subject of creation: St.Basil the Great, St. Ambrose, St. John Chrysostom, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and St. Ephrem the Syrian, finding that every last one of these brilliant theologians were what today would be called “creationists.” The pope was also able to read some of the nineteenth and twentieth century Orthodox commentators on the issue: St. Theophan the Recluse, St. John of Kronstadt, and St. Justin Popovich, all whom argued that the ancient tradition of the creation narrative could not be overruled by the consensus of secular atheists who claimed to be working under the banner of science. According to Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua, Pope Paul’s research on creation and geocentrism was extensive. In the 1980s, he claimed, the pope began a correspondence with an Athonite monk known as Elder Paisios, an outspoken critic of evolution. (My father’s notes indicate that he was trying to get copies of Elder Paisios’ letters from an archivist at Koutloumousiou Monastery on Mount Athos, a monk named Brother Ionáthan, but he does not appear to have succeeded. His last contact with Brother Ionáthan was in 1994. His notes indicate that Pope Paul’s letters were transcribed into Greek by a young rassaphore at the Godia monastery, and were signed merely as “Pávlos, a seeker”—so they may have been preserved, as the true identity of the writer was not known to Elder Paisios).

Elder Paisios of Mount Athos in an undated photo. He was declared a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church in 2015.

The pope and Elder Paisios shared with each other their thoughts on creation and geocentrism and the senses of scripture, and also on how the schism had adversely affected the Church, both East and West. They found themselves in agreement that it was a tragedy how, in the centuries since 1054, both sides had become infected with the disease of private judgement—a disease which blights all religion, philosophy, and politics, and which leads ultimately to atheism and spiritual death. In the West, private judgement was heralded most fiercely by Martin Luther at the Reformation, followed by Leibniz and Spinoza during the Enlightenment, and then Voltaire and Jefferson in birthing the twin Revolutions that tossed off monarchy. In the East, there was no longer a final religious authority to appeal to, and so their ranks became riddled with internal schisms and perpetual disagreements; in some cases there was disagreement over even which councils to accept. Both Pope Paul and Elder Paisios agreed that man’s fallen nature rendered him wholly unfit for private judgement, and that the only solution for everything that plagued him spiritually was to humbly submit to the ultimate authority. Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua said, “it was a fruitful exchange of ideas.”

The issue of private judgement is crucial to the current problems with traditional Catholicism. Most traditional Catholics have painted themselves into a corner by acknowledging Francis as the pope but refusing to obey him. They rely on their private judgement as to what they will accept; they are their own final authority. In an especially obscene arrangement, they reject, in all their pride, the exhortation of Pope St. Pius X:

Love the Pope! And how must the Pope be loved? Non verbo neque lingua, sed opere et veritate—not in word, nor in tongue, but in deed, and in truth (1 John iii, 18). When one loves a person, one tries to adhere in everything to his thoughts, to fulfill his will, to perform his wishes. And Our Lord Jesus Christ said of Himself, “si quis diligit me, sermonem meum servabit”—“if any one love me, he will keep my word” (John xiv, 23). Therefore, in order to demonstrate our love for the Pope, it is necessary to obey him.

Therefore, when we love the Pope, there are no discussions regarding what he orders or demands, or up to what point obedience must go, and in what things he is to be obeyed; when we love the Pope, we do not say that he has not spoken clearly enough, almost as if he were forced to repeat to the ear of each one the will clearly expressed so many times not only in person, but with letters and other public documents; we do not place his orders in doubt, adding the facile pretext of those unwilling to obey—that it is not the Pope who commands, but those who surround him; we do not limit the field in which he might and must exercise his authority; we do not set above the authority of the Pope that of other persons, however learned, who dissent from the Pope, who, even though learned, are not holy, because whoever is holy cannot dissent from the Pope.

And this is the paradox of traditional Catholicism: it accepts John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis as popes, but it refuses them the obedience which a Catholic is properly expected to give to the pope. The paradox can only be resolved if these men are in fact not popes in the first place. (No obedience, after all, need be given to an antipope).

According to Baltasar Fuentes Ramos, Pope Paul VI is a frequent reader of the Eastern Church Fathers. He told me this: “one of the most miraculous and incredible things about the coming restoration is that Pope Paul VI will finally reunite the schismatic Orthodox churches with Rome. This will happen after he consecrates Russia to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. The East will be converted and there will be a period of peace, as promised by Our Lady of Fátima. The ‘peace’ will not only be a period free of war, but it will also be a period of religious peace, where the two original spheres of Christianity, East and West, will once more be in harmony. And dissent and heresy will be quashed: the errors of evolution and heliocentrism will be solemnly and infallibly condemned. One of the most richly symbolic aspects of Fátima to keep in mind is that the Miracle of the Sun was an indicator, to everyone with eyes to see, that the sun is the orb which moves. Not the earth. The sun moves, and the earth is stationary. Just as the sun came to a halt in its circuit at the battle of Jericho, to demonstrate the Lord’s power (Joshua, x.13), so the sun danced at Fátima, to demonstrate the order of the heavens.” Fuentes said that much of the pope’s reading material pertains to Genesis, creation, the cosmos, and Revelation. He said, “it is a matter of the Alpha and the Omega. The beginning of time and the end of time are mystically connected. You cannot understand one without the other. Soon all things will be fulfilled.”