It was recently brought to my attention that the name I chose for this blog, “Pontifex Verum,” contains an inaccuracy. The correct term is “Pontifex Verus,” as pontifex is a masculine word and not neuter. I myself am not well-versed in Latin except for some common phrases, although as a traditional Catholic I have a great affinity for the sacred language of the Church, and wanted the blog title to reflect this. I asked an acquaintance how one would say “the true pope” in Latin, and “Pontifex Verum” was the answer I received. Alas, it was incorrect, and now I must shoulder the embarrassment and make the necessary correction. My gratitude to the kind and observant reader who pointed this out: we would not, after all, say “pontifex maximum,” but rather “pontifex maximus.” The title of the blog will be changed shortly, and I believe the URL will change also. I live and I learn. Thus it will be: “Pontifex Verus.”

Month: April 2017

Evan Morgan, 2nd Viscount Tredegar

Evan Morgan, circa 1930s. Poet, eccentric, and crypto-Luciferian infiltrator.

It does not escape the notice of this blogger that the subject of today’s post shares my surname. The subject also happens to have been a horribly iniquitous person. Fortunately, there is no direct kinship, as Evan Morgan begat no children. Also, my own line of Morgans have been split off from the Welsh Morgans for many generations, having been in North America since the late 18th century. We are the descendants of a fisherman named Thomas Rhydian Morgan who, along with his wife, Christina Kent Morgan, left Wales in 1786 and settled in the town of Shelburne in the maritime province of Nova Scotia, Canada. Therefore if I have any consanguinity with this hideous fiend, it is extremely remote. (Ouf!)

Something I was not well aware of until I read the testimony of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua was the surprising degree to which occultists, pagans, and devil-worshippers had infiltrated the Catholic Church. It is often said that Freemasons, communists, and various other enemies of the Church have, for decades, been worming their way into the ranks of the clergy, wreaking their subversion from within. And this is commonly accepted. But when it comes to tales of “Black Masses in the Vatican,” it almost becomes too much: for many Catholics, this is just too bizarre and unbelievable. It comes across like something out of a novel by Father Malachi Martin—and Fr. Martin was a suspicious character himself. His loyalties seemed to be forever shifting; sometimes he was a modernist when it suited him, and other times he was a traditionalist. He contradicted himself on many matters, and much of the time it almost seemed as if he was making things up as he went along. So whenever something carries “a whiff of Fr. Malachi Martin,” one is tempted to dismiss it as outlandish.

Such was my original reaction when I first began reading the transcripts of the Gagne-Bevilacqua interviews. I thought to myself: “purement fantastique. Incroyable!” But once I began researching his claims, to see if certain points might be corroborated, I was surprised to find that much of the people and events he mentioned adhere quite closely to recorded history. In the next post, I will provide a summary of the two weeks he spent in Rome in the summer of 1917. But first I would like to share what my research revealed—particularly as it regards his mention of a certain Evan Morgan: the unsavory and ghoulish person whose last name sends shivers up my spine: to think that he and I might share a common ancestor, somewhere back among the Morgans of Wales ages ago.

Evan Frederic Morgan was the scion of a wealthy family of the English nobility. Like many families of the aristocracy, the Morgans were what might be termed “fashionably eccentric and decadent.” In fact, they took their eccentricity and decadence rather seriously. His mother seemed to believe she was some sort of bird (an actual bird, that is, and nothing to do with the British slang for a good-looking girl). His grandfather, Frederick Courtenay Morgan, stood as a so-called “Conservative” Member of Parliament—and yet he was also a good friend of Richard Monckton Milnes, who owned one of the largest collections of Victorian-era pornography and was a patron of the poet Algernon Swinburne, a man of many perversions who composed much blasphemous anti-Christian verse, including a sneering condemnation of the Catholic Church entitled “Locusta.” Verily, the Morgan family was in the top tier of an English upper class that shewed an outward conservatism but led a secret life of terrible debaucheries.

Evan Morgan himself would continue the trend. As a young man at university, he converted to Roman Catholicism. But his conversion was insincere and superficial. What Morgan liked about the Catholic Church were its regal and extravagant trappings: the sublime atmospherics of the Latin Mass, the lace surplices and gold-tinged chasubles, the Gothic architecture, and the high ceremony of the papal court. What he did not like, however, was the Catholic faith itself. He was an awful despiser of Christ—so much so that he became an avid occultist. At around the same time he converted to Catholicism (the period when he was at Eton College at Oxford), Morgan also joined a Luciferian society known as the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), which is where he met and befriended the then-leader of the O.T.O, Aleister Crowley. Crowley became Morgan’s mentor; Morgan was Crowley’s ace pupil. Crowley deemed him “Adept of Adepts” (referring to a title which, according to my research, seems to be considered a high position in the rankings of ceremonial magicians. I did not research the occult too extensively; a Catholic must be prudent in these matters. The more one investigates the dark side, the more one runs the risk of coming face to face with the abyss).

Morgan thus began to lead a double life. On a typical Saturday evening, Morgan and Crowley would meet up in London, to smoke opium and to cruise the city’s squalid homosexual districts (both men were sodomites). Their night would culminate back at Crowley’s lodgings, where they would undertake “mystical” readings of the Kabbalah. Then they would set up an altar, with hexagrams, idols, and candles, and they would try out various unspeakable satanic rituals—first at midnight (“the witching hour”), then later at three o’clock (“the hour of the wolf,” or “the devil’s hour”). The next morning, a tired and bleary-eyed Morgan would show up for Mass at the Brompton Oratory to blasphemously receive Holy Communion. His close association with Crowley lasted between 1912 and 1913. During this time, Morgan informed Crowley that his ultimate goal was to summon a living demon. Together, they never succeeded. Crowley left the country in 1914 for Paris and then the United States. Morgan remained in England: writing bad poetry and keeping up appearances among the London aristocracy (when Aldous Huxley satirized high society in his novel Crome Yellow, he modeled the most immoral character after Evan Morgan). Morgan joined the Welsh Guards when the war broke out, and spent a year and half stationed in France. Most British soldiers were expected to spend three years in service, but Morgan used family connections to weasel out of a long-term obligation.

The young Evan Morgan during World War I, with his father Courtenay Morgan, the 1st Viscount Tredegar. The advantages of privilege: the elder Morgan spent most of the war on his private yacht, which the Royal Navy had converted into a floating hospital. Meanwhile the son served a shortened term in combat.

Upon returning to England from the front, Morgan rekindled his acquaintances in occult circles. On a visit to Glasgow, he began a friendship with a mysterious older woman named Myriam MacKellar, who claimed to be the Jewish wife of a wealthy Scot, and also to be an expert on the Hindu Vedic texts.

In 1916, Morgan made a pilgrimage to Rome, where he met up with an influential group of British-born clergy in the curia. He presented himself as a connoisseur of the liturgy, and he managed to charm them with his personality, a false display of piety, and a smattering of acquired expertise. Using his family’s wealth and status as leverage, he procured for himself a spot in the Vatican as a papal chamberlain.

It is important to note that no one in Rome was likely aware of his secret life as an occultist. It was 1916. Europe was in the midst of a catastrophic war. The doings of the eccentric members of the English aristocracy would simply not have shown up on the Vatican’s radar. It is also useful to consider that the pope at the time, Pope Benedict XV, was a holy pope and a staunch traditionalist. He was the author of the prophetic encyclical Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, in which he warned of the coming end of civilization—the natural result of Europe forgetting her Catholic roots and embracing the heedless nihilism of modern philosophy. (Miserere nobis; his assessment was correct). Nevertheless, the historical fact remains. This same man who decorated his home with inverted crucifixes and was a known friend of Aleister Crowley, also happened to be an actual Chamberlain of the Sword and Cape in the very court of Pope Benedict XV. Normally we might be able to look on this as nothing other than a tragic accident of history. But in early July of 1917, Evan Morgan traveled to Rome to mark the newly-minted refinements which had been made to the pope’s Prefecture. The Vatican had become a veritable convention of liturgical experts and enthusiasts. Also in Rome at this time were two young seminarians: Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua and Alessandro Falchi. What Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua witnessed there, he described as “the most harrowing event of my entire life. It will haunt me to the grave.”

Evan Morgan (left) with parrot, circa 1920s. Morgan owned a menagerie with many exotic birds, and was a trainer of carrier pigeons during World War II. He came from a family with an avian obsession. His mother, Lady Katherine, reportedly built bird’s nests to human scale at the family estate, Tredegar House, where she would sit in these nests like a hen. Her son’s poetry was rank: “The birds of love with plumage rare / Sped in circles ‘bout my hair.”

La Nuit Américaine

Before I commenced this blog, I was aware that there were several discrepancies between my source material and the more commonly-accepted chronology of Pope Paul VI’s survival. I have been graciously contacted by several readers in the Francophone world who have pointed these out—and the contradictions are more dire than I first realized. This poses a problem. There appear to be two serious differences between the versions, and they are differences which do not reconcile.

The first difference is that the mainstream narrative claims Pope Paul and his double were switched out interchangeably all the way up until 1975, when the double took over entirely. Meanwhile it says that Pope Paul stayed at the Vatican and did not go into exile until 1981. My material (mostly the testimony of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua) claims Pope Paul left the Vatican in 1972 shortly after declaring “the smoke of Satan has entered the Catholic Church,” and never returned. My material says he was being sheltered in a Cretan monastery as early as the mid-1970s, having spent a brief period in the city of Alexandria in Egypt.

The second area of contradiction is where the mainstream narrative claims Pope Paul was drugged in order to be made compliant in carrying out the modernist program of Vatican II. My material, however, says that rather than being drugged, Pope Paul was weighed down by a terrible demonic oppression, the result of a hex (or curse) which had been placed on him by occultists in 1935. It was this demonic oppression which gradually harassed and coerced the young Giovanni Battista Montini into modernism: first as an influential member of the Roman Curia, and later during his tenure as Archbishop of Milan. There would’ve been no need to drug him, as he was burdened by demons, and only very infrequently was he able (by the grace of God) to wrest himself from their awful sway.

There are also a few minor discrepancies, such as whether or not John Paul II knew of the double, and other quibbles. But these points are less troublesome. (In the case of JP2 being ignorant of the double, my material attests to it only via hearsay, so it doesn’t quite make or break the veracity of the testimony). Nevertheless, the brute fact of the two major contradictions remains. What to do with this? Was Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua just a crazy old man, rambling on at length over four days of interviews in a senile delirium? Or is his testimony at least partly reliable: dredging up portions of the truth insofar he could recall it, with the rest being culled from some nebulous half-dream or the vicissitudes of his mind’s whimsy? Or are the accounts of Pope Paul’s survival like the remembrances in the movie Rashomon, where the same event is witnessed by four people who give differing versions?

Another possibility was suggested by one of my correspondents. He remarked, “I do not know if I should believe this whole story, but if it is untrue, it is a very interesting novel.” This comment piqued my curiosity. I began to wonder if, somehow, the notes and transcripts and clippings I found in my father’s study were supposed have been the basis for some kind of creative writing project. I gave it some consideration—but in the end, it doesn’t seem likely. Firstly, I found them in a filing cabinet dedicated strictly to his journalistic endeavors. Secondly (as I have said of him before), my father was a rabid cinephile. He did, in fact, have some small portions of creative writing stored away in one of his desk drawers, but they were all the beginnings of screenplays—not novels or ficciones. My father, it seems, occasionally decided he would like to write for the movies. But shortly after starting these screenplays, he would give up on them. None of them go past twenty pages. And the subject matter is relatively light. They’re rather boilerplate, with nothing of the originality or innovation of the French New Wave which he so admired. The most “serious” of the lot is an espionage thriller about a woman in her forties in Soviet Russia named Lyudmila Trebetskaya who is a sympathizer for the West. The description of Lyudmila reads: “a savvy and attractive Moscow socialite greatly resembling Jacqueline Bisset.” It’s pure fluff, I’m afraid: John le Carré-derivative fluff. Father was an excellent and intelligent man, but sadly, creative writing was not among his talents (with all due apologies to my sire. It may also seem that I speak of him as if he’s deceased. He is not, but unfortunately he has Alzheimer’s disease and is “no longer there,” so to speak. I have no recourse to him in verifying the contents of the folders).

So no: Father does not seem to have focused his meager creative energies on anything nearly as extensive, intricate, or involved as the two massive manila folders documenting the long saga of Pope Paul VI. And besides, the material dovetails rather perfectly with too many actual events and persons of the twentieth century in the Catholic Church. The material does not present itself along the lines of, say, the sensationalized novels of Fr. Malachi Martin (which he termed “factions”—his portmanteau for blending fact and fiction), nor does it appear to be anything like an “alternative history,” such as the popular series The Man in the High Castle, or things of that nature. On the contrary: it all seems to have taken place in the very same past as our own, a past which has duly followed time’s arrow straight up to the present day. With that in mind, I do not believe the material to be a fiction.

I myself might be to blame for the “storytelling” quality. The transcripts themselves are long and rambling, and much of the time they can be downright banal. Thus far I have been attempting to trim off the tedium and give concise summaries of the history; only in the last post did I try to let the interview transcript speak more for itself. (Perhaps I will attempt to do more of that in the future, where portions of the interview are high in content. The first paragraph of the last post, however, where I summarized the childhood details of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua, was necessary, as I saw fit to condense into several sentences what it took him a couple pages of inconsequential chatter to relate).

Having taken into account the conflicts that exist between the narratives, I concede that my material is lesser. One of my correspondents informs me: “Fr. Basile Harambillet, a lawyer of the Roman Rota, maintained until his death in the early ’80s that he had been able to confirm that the true Paul VI was a prisoner in the Vatican throughout the double’s period of activity.” Admittedly, my material does not come from an esteemed canon lawyer. It comes from a self-described “simple man” who was essentially only the butler. However, I have decided that I will publish my material in full because I believe it is quite compelling in certain parts. Perhaps others will find it compelling as well. I think the testimony of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua contains much to recommend it. In fact, on the two main issues where we find discrepancies, I find it to be more satisfying. In charity, I would pose the following two questions:

1. Why was Pope Paul VI drugged, and why was he alternated with his double? Wouldn’t the modernist conclave in 1963 simply have elected a known modernist? It seems it would’ve been easier for them to elevate one of their own, rather than drug and incapacitate someone disloyal to the cause. Besides, Cardinal Montini had evinced modernist tendencies long before his coronation as pope. Was he also being drugged then?

2 . Why was Pope Paul VI kept prisoner in the Vatican until 1981? If he was miraculously protected from Freemasonic assassins for so long, why did he have to go into exile? The protection could’ve just been extended until the present day.

To my lights, my father’s material answers both of these questions rather pragmatically. First, it maintains that Pope Paul VI was not drugged into submission by the Vatican cabal, but that he was accepted by them as a longtime modernist, having shown progressive tendencies for more than twenty years. This was effected by a demonic oppression which lessened his free will and coaxed him into error and heresy.

Secondly, it says he went into exile almost as soon as his Vatican manipulus realized he could no longer be trusted to tow the progressive line. In 1968 he issued Humanae Vitae, which went against the modernist grain. From that point on, they lost their confidence in him, and lit upon the decision to replace him with a double, since there was already someone from his past who was known to bear a striking resemblance to him. When Pope Paul finally freed himself from his demonic oppression and brazenly told the truth (about “the smoke of Satan”), they promptly arranged to have him killed. He found out about the plot and went on the lam, which is when they propped up the double in his place. In fact, it was the double who exhibited “drugged up” behavior, for the simple reason that he had been a drug addict in the mid-1960s.

Pope Paul’s survival has indeed been miraculous, but rather than being miraculously protected, my material presents it as a “synergistic” cooperation between the divine will of God and Pope Paul’s own free will, which he recovered after he freed himself from his demonic oppression. Once he was out from under their influence, he showed himself to be, at heart, a good and holy man: faithful to tradition and hostile to modernism. And when he returns to Rome and takes up the fisherman’s chair, the Church will at long last have a good and holy pope.

All that said, I concede that most believers in the survival of Paul VI will probably be disinclined to accept my material in toto due to the differences. So be it. But hopefully it will unveil, at least, some portions of the truth which have heretofore lain dormant. Perhaps it can serve, not as an alternative, but as a modest supplement, however flawed. The existing narrative is persuasive on many counts—particularly where it coincides with the prophecies of Fatima (my own material hints not only at Fatima, but also a perennial Catholic prophecy known as the Three Days of Darkness, which I will get to later). I myself am grateful for being pointed to the truly exhaustive compendium of research, writing, and translations undertaken by a brilliant documentarian Français named Jean-Baptiste André. His work forms the most comprehensive resource on the internet on this subject. With his permission, here are several links to his websites.

Pope Paul VI’s Survival and the Secret of Fatima (English)

La Survie du Pape Paul VI (French)

Paul VI and the Mystery of Iniquity (French movie w/ English subtitles)

My original inclination still remains: to publish an entire summary of my father’s material. I will put it all out for the consumption of anyone who might still be interested, and decidat lector—my Latin is probably garbled there, but: “let the reader decide.” Let everyone separate the wheat from the chaff in this blog according to however they see fit. In the words of a “tedious old fool”: “If circumstances lead me, I will find / Where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed / Within the centre.” (Wm. Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2).

At the Brescia Seminary, 1916-17

Claudio Cesare Gagne-Bevilacqua was born to a moneyed family in Iseo in 1898, in a third-story bedroom in one of the city’s stateliest mansions. His father was a railway executive for a private line owned by a Lombard Marquis. The Gagne-Bevilacquas had profited handsomely from the 19th century industrial boom in northern Italy, and the consequent expansion in rail. (It was a fortuitous time to be a railway executive). The baby’s Christian name was given to him after the Roman emperor Claudius Caesar: the boy had been born with unequal leg lengths; his left leg was a full four centimeters shorter than his right. It was clear that the child would eventually walk with a distinct limp; the emperor, who was club-footed, had also limped. “My father was very fond of Roman Antiquity, and he had a morbid sense of humor also,” recalled Gagne-Bevilacqua of his papà. “And therefore I was Claudio Cesare. Besides, I was the ninth child, and I was the runt. At that point, I suppose, my parents could be cavalier with names.”

Roger Morgan (the father of this blogger) met with Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua in January of 1986 in Turin. The following is excerpted from his notes and transcripts of his first visit to Gagne-Bevilacqua’s apartment.

He is a short man, and squat; coarse-looking and swarthy—almost dwarfishly short, in fact, perhaps five feet tall. My first impression is of Toulouse-Lautrec (had Toulouse-Lautrec, perhaps, lived into old age). He walks with a distinct hobble owing to a birth defect in his left femur. His left shoe has a modified sole to correct for this, but it helps only so much. Nevertheless he has an elfin agility and sprightliness, even for a man of his advanced years (he is eighty-seven).

I am impressed at the strange grace and deft with which he maneuvers around his flat. Meeting him and observing him, one is reminded of two fictional bell-ringers: Hugo’s Quasimodo and Huysmans’ Carhaix. He has Quasimodo’s simian dexterity in spite of his handicap (I can easily picture this old fellow swinging from the ropes of a bell tower), and he has the unassuming piety and good-sense traditionalism of Carhaix. One imagines him excelling in his lifelong service as a valet. This man exemplifies old-fashioned sturdiness and efficiency.

He goes to a bureau, opens a drawer, and locates an old photograph. He hobbles back over and hands it to me. It’s a relic of a picture, with all the scratches and speckles of a daguerreotype: it’s the entering class of first-year students at the Brescia Seminary in 1916, the order of acolyte. He doesn’t need to point himself out—I can locate him immediately: a dwarfish little thing standing in the front row, wearing a cassock too long for him that falls onto his shoes, one of which has a lifted sole. He’s probably the best-looking young man in the class, though. The youthful Gagne-Bevilacqua possesses an oddball handsomeness: a darkly aristocratic look (thick brow, heavy-lidded eyes, and thin lips) tempered with a droopy hangdog tinge: a nose slightly too big and a face slightly too long. And then I realize who he truly reminds me of: Al Pacino. In this photo he is the early Al Pacino, circa The Panic in Needle Park. I remark on this.

RM: Begging your pardon, Signore. Has anyone ever told you you resemble the actor Al Pacino in this picture?

CGB: (shakes head) I do not know who this person is.

RM: He’s a famous American actor. Surely you’ve seen, or heard of, the Godfather movies?

CGB: No. I am sorry. I have not been to the cinema since the 1960s. La Dolce Vita. I found it scandalous.

My father was a massive cinephile, so it’s unsurprising he would steer the conversation in that direction so soon. Two things stand out to me, however, reading these notes and transcripts more than thirty years later. The first is that, in 1986, the Godfather movies consisted of only two installments. A third entry in the series came out in 1990, and part of its plotline included a conspiracy to murder John Paul I. The reasons for the assassination in the movie are purely fictional (and completely wrong), but it is interesting that the movies were mentioned here in passing since, on the fourth day of their interviews, Gagne-Bevilacqua would inform my father of the true details of the actual murder of John Paul I in 1978. The second thing is that my father had been struck by the physical resemblance of two different men born generations apart. What Gagne-Bevilacqua pointed out to him next, however, was even more striking: the uncanny similarities between two of the boys in the very same photo. On the far left was Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI. In the middle of the right side was Alessandro Falchi.

We can only surmise at what the young Montini must’ve thought upon first meeting his doppelgänger at seminary. In mythology, the doppelgänger represents the dark half—and this aspect, indeed, would prove true: Falchi would turn out to be wicked soon enough. And just as in Dostoevsky’s story of a man who meets his double, the evil twin in this case would eventually come to bedevil his counterpart, overtaking his life and eventually replacing him altogether. But a doppelgänger is also said to be a portent of death (when the poet Shelley saw his double, the other Shelley pointed wordlessly to the Tyrrhenian Sea where he would eventually drown). Not so with Montini’s counterpart, however. Alessandro Falchi died in 1978; Pope Paul VI is yet still alive.

At the time, Gagne-Bevilacqua was not privy to how Montini himself felt about any of this. “I knew Montini hardly at all during my year in seminary,” he said. “He had some health problems, and he did not live on the campus. He stayed at home, and was driven back and forth each day. I don’t remember much about him. He was of average intelligence, I would say. Generally well-liked. I’m afraid he didn’t make much of an impression at the time. There was no indication he would one day become pope. What I recall mostly is that he looked so much like Falchi. Everyone was amazed at how they could almost pass for twins. And Falchi, of course, I got to know very well. We were assigned to share the same dormitory room.”

According to his first-year roommate, Falchi did not care for Montini. Much of their physical similarity was remarkable: the same-shaped jawline, identical pairs of piercing eyes, and equally aquiline Roman noses. But Falchi had poor eyesight, and wore a thick and unflattering pair of glasses. He also wore his hair extremely short, shorn down to just a coarse stubble—because to grow it out would reveal tight kinky curls, which he hated. “He despised his hair. He was terribly vain,” related Gagne-Bevilacqua. From the transcript:

CGB: He was very superficial. Perhaps it bothered him that Montini had nicer hair and didn’t wear glasses. I don’t know. But for some reason he resented him. Falchi was fixated on his own looks. He was frequently in front of the mirror, you see: shaving his chin, tweezing his nose hairs, plucking his brow. I was appalled he was even in seminary in the first place. He was obsessed with his looks, and he seemed determined to commit as many sins of the flesh as he could. I knew for a fact he was carrying on with a lower-class girl named Lia who lived in town, and that he impregnated her. She kept the paternity of the child a secret, and she and her mother raised it on their own. Falchi’s only contribution to the child was to name it Federico.

RM: After Engels, I presume? You’ve told me Falchi was a communist.

CGB: No, after Nietzsche. He became a communist much later. Who knows what he really believed. Falchi was simply a sieve, in my opinion, catching anything which was contrary to the faith, and letting anything that was pure slip through. Nietzsche, modernism, Satanism, communism, Kabbalah, Hindu paganism—whatever he could get his hands on, I’m telling you, as long as it was anti-Catholic. Years later, in the forties, he fathered two other children. Consider their names: Benito, after Mussolini, and Giosuè, after Carducci.

RM: Carducci?

CGB: He was an anticlerical poet of Italy. Falchi loved his poem called Inno a Satana—“Hymn to Satan.” I believe that poem sums up Falchi the best. It is a simple paean to individuality and unbridled freedom. What Falchi despised most was the authority of God and the Church. At one point I decided I’d had enough of his impiety, and I reported his behaviors to one of the masters. But nothing was ever done. I thought to myself, “how is it that the rector and the administrators are letting this abomination stay on?” But he was very intelligent, you see. I think that’s what must’ve endeared him to the masters. I suppose even in those early days he was quite capable of putting on a façade. The Falchi I knew was a reader of Nietzsche and Carducci. He even kept a pet tarantula in a small aquarium in our room. He told me the tarantula had some important symbolism in Nietzsche. I forget the particulars. Do you know what it is?

RM: In Nietzsche? No, I’m unfamiliar.

CGB: It does not matter, I suppose. But here is the thing: secretly he was reading these abhorrent writers, but outwardly he was projecting the image of a keen student. His knowledge of the scriptures was encyclopedic. And he could recite long passages of St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae verbatim. Scholasticism, you see, was the cornerstone of seminary education at this time. The legacy of Leo XIII and his Aeterni Patris were still reverberating throughout the Church. This is the main reason I did not last past my first year in seminary.

RM: Scholasticism?

CGB: Yes. It’s very involved and analytical. It requires an elite mental faculty. But me—I do not have such acuity. I am a simple man. My mind is not suited to it.

RM: You … seem very intelligent to me, Signore.

CGB: Oh, I am not a complete dunce. I get by well enough okay. My masters at seminary, I think, were hoping I would be like St. John Vianney: far from a star pupil, but dedicated enough to make it through. Well, it was not to be. The Curé of Ars, I believe, had troubling learning Latin. His teachers were concerned he would never learn to celebrate Mass. My difficulties were just the opposite. Latin was my sole advantage. I was mastering the liturgy quicker than anyone. I have always had a knack for languages. My father’s library was helpful in this. I was reading Virgil, Cicero, and Catullus in Latin when I was a boy of fourteen. Not to brag, but it is the truth. I was good at Latin, but poor at all else. My deficiencies were especially theological. I could not find my way through that Summa. It was a labyrinth, and I was constantly getting lost in it. With all respect to the Angelic Doctor, it gave me a headache. Meanwhile I was finding much to love in the classical Stoics. Their language was plain. Their ideas were easy to grasp. While Falchi stayed up late studying his Nietzsche in our room, I was reading Seneca and Marcus Aurelius in Latin, and Epictetus in Greek. I realized that if there was any kind of philosophy meant for me, it was practical philosophy. I knew I was suited for a more modest vocation. Had I continued on at seminary, Scholasticism would’ve been my bane: I would’ve resented it, and I would’ve made a mediocre priest, at best.

(At this point, Gagne-Bevilacqua gestures to his shorter leg).

CGB: As you might guess, Epictetus in particular had a profound influence on me. He was a kindred spirit. First, a cripple. Second, a Stoic. And third, of all the Stoic philosophers, he was the one most preoccupied with God. I wonder if he was ever preached the gospel. Do you suppose he ever heard it? I doubt he did, because I think he would’ve received it warmly. He would’ve been one of the greatest early Christian philosophers.

There then followed a long meander in the conversation. Gagne-Bevilacqua made tea, and went on at some length about the correct method & materials for brewing a proper cup of tea—having mastered it, he said, over the course of his career. In short, his method was this: Ceylon leaves, loose (never bagged—bagged tea has “an aftertaste of paper”), steeped in a glass pot for precisely four minutes in water with a temperature of 70°C (one must use a thermometer). My father then took the earlier mention of philosophy to segue into a digression on the Catholic philosophical themes in the films of Robert Bresson, his favorite director. He was eager to disabuse Gagne-Bevilacqua of his contempt for the cinema, conceding that the industry was largely wretched, but insisting that it was a high art form when placed in the right competent and thoughtful hands. They eventually returned to the subject of Gagne-Bevilacqua’s seminary year.

RM: Well, if you were a liturgical prodigy as a seminarian, then I know you must innately appreciate the language of cinema at its purest: sight, sound, and symbols.

CGB: Perhaps. But it was my talent for the liturgy that eventually took me to Rome, which is where I received the shock of a lifetime. It was there that I first became aware of the awful tentacles which had already, in 1916, begun to work their way into the Church. My roommate Falchi—his brand of anti-Catholicism was rather aimless and bored. I don’t think he had any direction or focus. He just hated authority and bristled against God. But when we got to Rome, I came into contact with some persons who had serious intentions indeed. These were the real servants of hell. I shudder to even remember it.

RM: What brought you to Rome?

CGB: Pope Benedict XV, in a sense. The Holy Father was very much a high churchman. He had recently made some reformations and refinements to the college of the Magistri Caerimoniarum—the liturgical experts of the papal household, you see. Our Pope Benedict was keen to instill, in the clergy and the seminarians, a real appreciation for the pontifical liturgy. That summer, some of the northern seminaries were asked to send a few of their acolytes to Rome, to study for two weeks with a visiting liturgical consultant, Monsignor Matteo Gallo. I was the obvious choice from the Brescia Seminary. But they were supposed to send two students. When Falchi learned of my appointment, he asked one of his masters if he might go as well. The answer was yes. And so we went. And let me tell you, when I got back from Rome and returned to the seminary, it was only to collect up my things and leave. What I saw while I was at the Vatican will haunt me forever.

At this point, Gagne-Bevilacqua became reticent to divulge more. He attempted several times to change the subject, at one point successfully coaxing my father into another long digression about cinema. They did finally return to the chronology of relevant events, which I will excerpt and summarize in the next post.

It will remain forever unclear what symbolism the young Alessandro Falchi discovered in Nietzsche’s tarantula. According to Jung, “the tarantula represents one of the many aspects of the inferior man, and if the inferior man bites him, and pours his shadow into his face, it has surely gotten at him and then he becomes the shadow. He himself now plays the role of the tarantula: he becomes poisonous, and his ressentiment is manifest even against people to whom he cannot deny a certain amount of merit.” But this is cryptic blather, and not of much help. Nietzsche’s own passage is equally enigmatic:

“And then the tarantula, my old enemy, bit me. With godlike assurance and beauty it bit my finger. ‘Punishment there must be and justice,’ it thinks; ‘and here he shall not sing songs of enmity in vain.’ Indeed, it has avenged itself. And alas, now it will make my soul, too, whirl with revenge. But to keep me from whirling, my friends, tie me tight to this column. Rather I would be a stylite even, than a whirl of revenge. Verily, Zarathustra is no cyclone or whirlwind; and if he is a dancer, he will never dance the tarantella. Thus spoke Zarathustra.”

Next post in the chronology of events

Next immediate post: a digression to address some questions and comments

Queries from Eire

I was recently contacted, via my Gravatar account, by an interested reader of this blog—a very nice woman in Ireland named Fionnula. Because her concerns seemed broad enough that they might be shared, I’ve decided to respond publicly in order to quell any similar consternation which other readers might have. My thanks to Fionnula for allowing me to reproduce parts of her message.

Fionnula first inquired as to where I was getting my information about Alessandro Falchi, as well as the living Pope Paul VI in Portugal. She told me frankly: “I can’t find any corroboration for these things, so I’m sorry but I’m not too inclined to believe it.” And that is fair enough, Fionnula; I concede that the corroborating material on the internet is somewhat scarce regarding Alessandro Falchi or the living pope, although you can certainly find a portion of traditional Catholics who believe in the firmamentum of it (i.e., a succession of false popes, and an imposter Paul VI. The overall thesis is not new by any means). The impetus for this particular blog, however, has been to present a trove of material which has been heretofore undisclosed. “Light will be thrown” (to paraphrase the heathen Charles Darwin) on a secret history which has languished for too long in the shadows—hence why my introductory post ended with “Fiat lux!” So I do have sources. To explain shall require a small amount of background material.

My father, Roger Morgan, was a Canadian-born freelance journalist who covered the Vatican, in both English and French, during the 1970s and 80s. Most of his reporting was done for UPI. He was not the “young journalist” mentioned in my previous post when I referred to President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (Father would’ve been in his fifties at the time), but he was present at that very same press conference. Father is still alive, actually, but he is ninety-one years old now, rather immobile, and dealing with some serious health issues. Due to these circumstances, he moved into a nursing home several years ago. My siblings and I were cleaning out his apartment after the move, and the responsibility fell upon me to pack up his study and personal library. Going through an old filing cabinet, I found two thick manila folders, overstuffed with pages both handwritten and typed.

The first folder contained transcripts of an interview Father had recorded with a man named Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua over the course of four afternoons in Gagne-Bevilacqua’s apartment in Turin in the winter of 1986. Gagne-Bevilacqua had been the personal assistant to the pope from 1963 to 1978. This fact is quite astounding: his tenure spanned not only the regnum of the true Paul VI, from 1963-72, but also the usurpation reign of Alessandro Falchi, from 1972 until his death in ’78. Simply put, Gagne-Bevilacqua saw everything transpire over those fifteen years. He knew it all.

Fionnula also expressed some skepticism as to this very person. She wrote: “by the way, I looked up the personal assistant to Paul VI and it was either Pasquale Macchi or John Magee.” Permit me a correction in terminology here, Fionnula: the two men you have mentioned served in the capacity of private secretary; that is, they assisted the pope in clerical matters—managing correspondence, speeches, encyclicals, and suchlike. It’s a highly esteemed position in the papal office. Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua, however, was the pope’s personal assistant. A different title altogether, and generally less esteemed. This is a position that would be similar to our notion of a valet, butler, or dedicated manservant. The personal assistant was responsible for quotidian affairs: making sure the pope’s needs were carefully tended to in terms of clothing, meals, travel, &c. For example, the personal assistant would see to it every evening that the pope’s outfit for the next day was laid out for him, cleaned and starched and nicely pressed. In the morning he would bring the pope his breakfast and coffee on a tray, with several newspapers tucked under his arm. Throughout the day he would fetch various things and contact various persons at the pope’s request. He was, in short, the kind of man who wears a dark suit and white gloves, who is never obsequious or fawning, but rather that rare and valuable breed of companion: a practical, straightforward, and quiet man of common sense and good decorum. I do not know if the position even exists any longer. In the decades following Vatican II, the Catholic Church has striven to lose some of her “anachronistic” trappings. The papal valet position may’ve been eliminated as a result. The current pope (or antipope, actually), Francis, prefers to make a big show of how humble and impoverished he is. At the beginning of his reign, Francis turned up his nose to the lavish papal suite in the Vatican apartments, opting instead to live in a quaint room in a boarding house. It’s unlikely Francis would have a personal assistant. He would probably view it as too haughty. But the position existed as recently as 1978, when it was filled by Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua. My father’s interview with him forms the bulk of my primary source material concerning the personal histories of Pope Paul VI and Alessandro Falchi.

The other manila folder I found in my father’s office contained notes, transcripts, newspaper clippings, and information pertaining to the well-known case of a young woman in Bavaria named Anneliese Michel, who underwent a series of exorcisms in 1975 and 1976. Her possession ultimately resulted in her death. Following a legal trial in which her parents and her priests were prosecuted for negligent homicide, the Catholic authorities in her diocese began a campaign of disinformation, attempting to spin the events as a tragic confluence of mental illness and religious hysteria. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Nota bene that when Anneliese’s body was exhumed, her exorcists were not permitted to view it. Instead it was simply announced, with no accompanying visual evidence, that the body was in a state of decomposition. This was intended to refute the idea that Anneliese is an incorruptible—since many traditional Catholics, including this blogger, believe her to have been a martyr. This much is undeniable, though: the Catholic diocese objectively reversed its position. Originally it deemed Anneliese possessed, and granted official permission for the exorcisms. Only after Anneliese’s death, and only after certain functionaries in Rome became aware of what the exorcisms revealed, did they attempt to sweep it under the rug with claims of mental illness. But despite their efforts, the case did not go away. It eventually formed the basis for a successful 2005 film called The Exorcism of Emily Rose. Though highly fictionalized, the movie can be recommended, as it provides a mostly sympathetic treatment.

One of the priests who exorcised Anneliese was Father Arnold Renz. Fr. Renz was the subject of the second folder of interview transcripts: my father spoke with him in Würzburg, Germany in April of 1986. My father’s notes describe Fr. Renz as “thoughtful,” “pensive,” “ruminative and wise,” and “burdened with his tragedy.” It is clear that Fr. Renz’s awful confrontation with hell never quite left him. When my father met with this holy priest, he met a man brooding heavily on the past. The interview reveals that when the exorcism rites began, the demons informed the two priests performing them (Fr. Renz and a Father Ernst Alt) that they could not quit Anneliese’s body until they had first made a series of revelations. Thus began a long and torturous ordeal for Anneliese—one which she did not survive—since every time the exorcists commanded the devils to leave, they were unsuccessful. Instead the priests were constrained into coaxing out the revelations.

The demons were frequently resistant, hostile, and uncooperative. They wanted to maintain their possession for as long as they could. At other times, they could be boastful and derisive. The most significant such instance is this: at one point, they lorded it over the priests that they (the priests) were unwittingly in communion with a false pope. They also taunted the exorcists by crowing over Satan’s perverse triumph at Vatican II: infecting the Church with modernism and foisting an ugly new liturgy on the faithful. (Not coincidentally, Anneliese’s family were devout and conservative Catholics who attended a Latin Mass, and cared hardly a whit for the innovations of the council. Anneliese herself mentioned that if she died, she hoped her suffering might atone, in some small part, for the willful apathy of so many young Catholics, and the wanton heresy of so many modernist clerics). In the decade between Anneliese’s death and his interview with my father, Fr. Renz had investigated the demons’ astounding claim of a false pope. Initially, he had been hesitant to think it was anything other than fiendish braggadocio. When his research concluded, however, he had become wholly convinced that the satanic plot to destroy the Catholic Church had successfully set up a line of heretical antipopes.

Portions of Anneliese Michel’s exorcism tapes are available online; others are not. Sadly, a search on YouTube yields a good many videos focused on the more lurid and horrorshow aspects of the exorcisms—and seem to carry a disrespectful sense of gawking at a poor soul in torment. The audio is nevertheless unsettling. Kyrie eleison.

The funeral of Anneliese Michel. Father Renz is second from right, holding his Missale Romanum and a vial of holy water. The antiphon for the sprinkling & incensing of the grave is the Ego sum resurrectio: “I am the resurrection and the life: she that believeth in Me although she be dead, shall live, and every one that liveth, and believeth in Me, shall not die for ever.”

Corollary to the case of Anneliese Michel is the record of exorcisms performed on a Swiss woman known as “Rita B.” from 1975 to 1978. (It will be of interest to traditional Catholics that the approval for these exorcisms came from Archbishop Lefebvre himself). In this case the revelations were even more explicit: the demons unveiled that there was a plot against Pope Paul VI and that he had been replaced by a double. Ten priests in total conducted the exorcisms, the transcripts of which have compiled into a book in French by Jean Marty, called Avertissements de l’au-delà à l’Église contemporaine (Warnings from Beyond to the Contemporary Church). Not surprisingly, the Baysiders (the persistent cult of followers of Veronica Lueken, who we met in an earlier post) have latched onto these exorcisms. One of the Baysider websites has an English translation up. As I warned before, however, they have their own baffling view of the situation, so go down the rabbit hole of their conspiracy theory at your peril. But it will be clear to anyone who researches it that the revelations in the Swiss exorcism case contradict the revelations from Bayside on several counts. In fact, the the book’s editor, Monsieur Marty, is not a Baysider in the least. He believes (quite correctly) that Paul VI still lives.

My apologies for the length of this response, Fionnula. And I have still not answered your question as to the source of my information for Pope Paul’s current existence in Portugal. Due to time constraints, that will have to be undertaken in a separate post—and a later one at that, since the chronicle of Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua merits telling first.

Surrexit Dominus vere, alleluia!

Today, of course, is Easter, when the Catholic Church celebrates the Resurrection of Our Lord. The pope, every Easter Sunday, gives one of his biannual Urbi et Orbi addresses at St. Peter’s square. Francis has already given his. He issued a fine condemnation of Saturday’s suicide bombing of refugees in Syria. Francis is an interesting person; he will be discussed later, and in great detail, as I attempt to fully unspool this long history I’m calling “the Saga of Pope Paul VI.” For now it need only be said that Francis is one of the two popes (or antipopes, more correctly) out of the four since 1978 who were actually aware of Paul VI’s survival and exile. The other one was John Paul I (Albino Luciani), who died after only thirty-three days in office. But more on that, also, in the future.

One of the more surreal pieces of trivia surrounding Francis and Pope Paul VI is the fact that on October 19th 2014, Francis presided over the solemn beatification of Paul VI. He publicly and formally decreed a man to be in heaven whom he knew to be alive. It is a fantastic charade that recognizes no bounds. And with that, a Happy Easter to all.

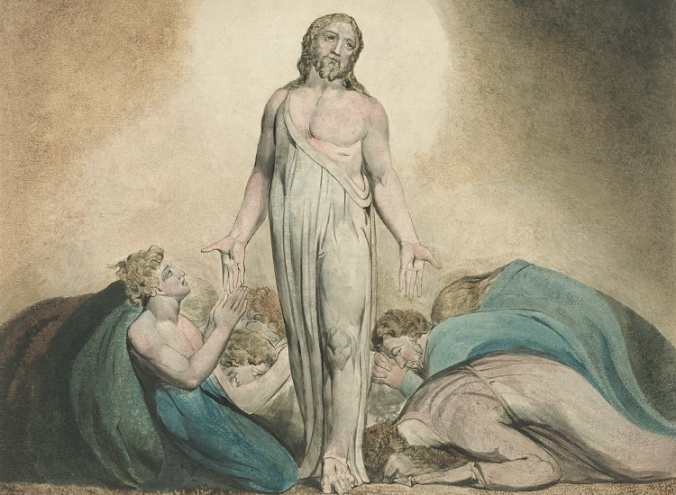

William Blake, Christ Appearing to His Disciples After the Resurrection (c. 1795)

Answering another frequent objection: Paul VI was a modernist heretic

Non-Catholic readers of this blog may have some confusion over the use of the term “modernist” since, in common parlance, modernism typically denotes a literary and artistic movement in the first half of the twentieth century, evoking things like the poetry of T.S. Eliot or the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. In Catholicism, however, modernism refers to a movement originating slightly earlier (in the late nineteenth century) and having to do with things like critical readings of the bible, or attempts to harmonize the faith with contemporary movements in philosophy and culture—to rid the Church of her reliance on antiquated dogmas, and to re-imagine the faith in purely modern terms. It was denounced as soon as it began. The most famous condemnation is Pascendi Dominici Gregis, an encyclical issued in 1907 by Pope St. Pius X. “We have witnessed,” he wrote, “a notable increase in the number of the enemies of the Cross, who, by arts entirely new and full of deceit, are striving to destroy the vital energy of the Church, and to utterly subvert the Kingdom of Christ.” He noted, too, that those who sought to destroy the Catholic Church were now doing their work from within: “the partisans of error are not only among the Church’s open enemies,” he observed, “but also—most dreaded and deplored—in her very bosom, and are all the more mischievous the less they keep in the open.”

Pascendi Dominici Gregis signaled the alarm and put up the bulwark; alas, it failed to deter the modernist beast. There were so many dissidents in the Church, of so many different stripes, that the movement became a hydra, a many-headed monster—if you chopped off one head, two more grew back in its place. In the end, the spiritual cancer of modernism metastasized, and nearly the entire hierarchy wound up being converted. A half a century after Pius X denounced it, most of the prelates in the Catholic Church were unrepentant modernists—including the subject of this blog: the then-Archbishop of Milan, Giovanni Battista Montini. When the Second Vatican Council opened in 1962, even the pope himself was a modernist: John XXIII said he wanted to “throw open the windows of the Church to the world and let the fresh air blow through.” Out with the old, in with the new. When the council closed, modernism was solemnly enshrined in its documents. Religious liberty, ecumenism, tolerance, and liturgical renewal were the order of the day. And meanwhile, Abp. Montini had been elevated to the papacy following the death of Pope John: he was Paul VI now. He gave an enthusiastic public speech at the close of the council, heralding “a unique moment: a moment of incomparable significance and riches.” No one gave Vatican II a greater endorsement than the pope who gift-wrapped it to the world.

So yes, Pope Paul VI was a modernist heretic. But understand this: it was only outwardly. It was not of his own free will. In truth, a terrible curse was upon him. Twenty-seven years before he became Pope Paul VI, Giovanni Battista Montini crossed paths with a dark and elemental evil. In time it overtook him; he was helpless but to become its pawn. Just as Satan “entered into Judas,” an unspeakable goetic malignancy had taken hold of Montini’s soul and oppressed him. Daily he was besieged by a throng of unrelenting demons, like the riot of devils in the many renderings of the Temptation of St. Anthony. So long as he did their bidding, they relented, and he was at ease. The moment he tried to defy them, however, they would assail him with gruesome horrors and unendurable physical anguish. In the following few posts I will explain. We will have to go back, initially, to the period (1916-1920) when Montini was in seminary, where he first encountered Alessandro Falchi; and then later to his time as a member of the Roman Curia in the 1930s, where he ultimately met the daemon that would possess him for three decades. We will have to examine some aspects of Edwardian occultism, as well as Italian communism and Freemasonry. But the objection will be answered: Pope Paul VI was under a terrible sway, one that he did not begin to emerge from until 1968, when he shocked the Vatican and the world by issuing his encyclical Humanae Vitae, a document that boldly reaffirmed the Church’s traditional stance on birth control. It was a surprising conservative about-face from the progressive gospel which had been proclaimed at the council. Virtually everyone had expected Paul VI would take a softer stance. And yet he did not. By 1972, the pope was free of his curse completely, and he publicly and defiantly proclaimed to an audience the unalloyed truth: “the smoke of Satan has entered into the Catholic Church.” He really did say that. You can look it up. And in doing so, he signed his own death warrant. Two months later, he was in exile.

Epigraph to The Wasteland (1922). “And when the boys used to say to her, ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she replied, ‘I want to die.’”

Dispatches from Bayside

The theory that Pope Paul VI was replaced at the Vatican by an imposter is not novel. It is by no means original to this blogger. It is, in fact, somewhat well-attested to over the past four decades. One of the earliest and best-known attestations in North America was made in the late 1970s by Veronica Lueken of Bayside, Queens in New York (here is her Wikipedia entry; here is a website operated by a group of her devotees called St. Michael’s World Apostolate, and here is another called These Last Days Ministries. This blog does not endorse either organization).

Mrs. Lueken claimed to be a Marian visionary, maintaining that she had seen countless apparitions, not only of the Blessed Mother, but many saints and angels as well. In one of her messages, Mrs. Leuken related that the Virgin Mary had appeared to her and informed her that the pope, Paul VI, had been murdered by a satanic cabal in the Vatican. According to Mrs. Lueken, Mary told her the cabal had placed an imposter on the throne of Peter—a communist look-alike who had been worked on by the finest plastic surgeons in the world, sculpted into a remarkable replica. “My child,” said Mary (allegedly) to Mrs. Lueken, “shout this from the rooftops!” The result was that Mrs. Lueken received a swift condemnation from the Diocese of Brooklyn. Her visions and revelations were deemed not credible, and harmful to the faith.

It is the opinion of this writer that the Diocese of Brooklyn was correct. Mrs. Lueken’s visions couldn’t have come from heaven, because heaven does not make errors. And Mrs. Lueken was flatly wrong: Paul VI had not been murdered. He had, it was true, been replaced by an imposter. But he was nevertheless living. He would’ve been able to say, as Mark Twain had quipped, “reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” And like Twain’s characters, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, the pope had actually watched his own funeral (not from a choir loft, however, but on a squat little portable black-&-white Brionvega television in the Milan apartment of an elderly couple he knew from his tenure as Archbishop there). And at the time of Mrs. Leuken’s revelations, Pope Paul had fully settled in to his secret life in exile. He was being sheltered by a group of Greek Orthodox monks on the isle of Crete, wearing the coarse cassock and skufia of Byzantine monastics, having grown out his beard to a full, bristling, and wild Rasputin length (the Italians are a hirsute race, so within a few years he was quite able to rival his Greek compatriots in their ages-old habit of growing untamed Moses beards). Even the most careful observer would hardly have recognized him there, emerging from his cell in the morning with his head solemnly bowed, joining the slow, shuffling procession of dark robes to the chapel to chant the ancient prayers of the Psalter. (I might be getting ahead of the story with all this. In later posts, I will tell of how Pope Paul initially learned of the plot to murder him, how he managed to escape from the Vatican, and where he journeyed afterwards; the report comes from his personal assistant, Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua. The salient fact is this, though: at the time of Mrs. Lueken’s revelations, Pope Paul VI was very much alive).

So Mrs. Lueken’s story was only half right. But it’s relevant, for our purposes here, that an obscure housewife in Bayside, Queens was already articulating the idea that the Pope Paul in Rome was not actually the real Pope Paul. What probably happened is that Mrs. Lueken caught a whiff of a rumor which contained a nugget of truth. And rumors were really beginning to make the rounds by the middle of the 1970s. The imposter, whose real name was Alessandro Falchi, was exhibiting catatonic and strange behaviors.

Soon, over the span of several posts, I will provide a more detailed biographical sketch of Alessandro Falchi. Suffice it to say for now that by the time he took up his role as “Pope Paul VI,” he was a walking casualty of a hideously sinful lifestyle. Falchi had always been a libertine: he was a man of rapacious and indiscriminate sexual appetites. In modern parlance, we might label him a “bisexual,” although even that might be too restricting a term. He had relationships with women and men, mostly men, and sometimes even with those woe-begotten persons who exhibit the genitalia of both sexes, called hermaphrodites. Falchi was an ordained Catholic priest, but privately he was an occultist; in the mid-1950s he requested a position in Bombay, India (now known as Mumbai) in order to increase his knowledge of the Sanskrit language and to study the Vedic ritual texts. In a padlocked off-limits room in his rectory, he erected a shrine (candles, altars, flowers, and statues) to the Hindu monkey-god Hanuman, to whom he sacrificed a bowl of ghee every evening. While in Bombay, Falchi fell in love with a hijra prostitute named Saraswati. It is unclear whether Saraswati was a male passing for female, or a hermaphrodite, or something else. Falchi told Gagne-Bevilacqua, “my Saraswati eluded definition.” Fairly repulsed, Gagne-Bevilacqua did not press the issue. What Saraswati did do, however, was to give Falchi the venereal disease syphilis, which slowly began to ravage his once-formidable mind.

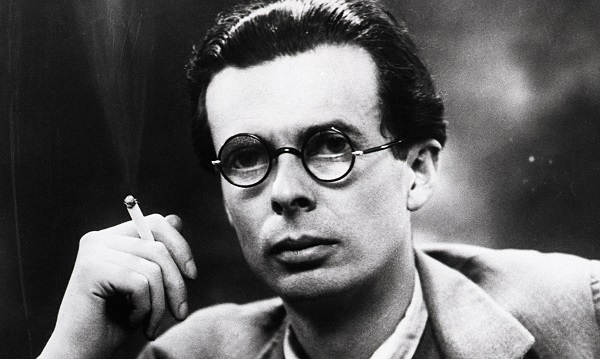

After his stint in India, Falchi was laicized (details to come) and ended up in southern California in the 1960s, wearing a casual wardrobe purchased in Bombay: leather sandals, earth-toned trousers, madras shirts, and mala bead necklaces. He fell in with the haute crowd of British expatriate intellectuals living there, including Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood. Most of these men were Indophiles; Falchi managed to ingratiate himself among them with his competence in Hindu religious matters. He impressed Huxley by recounting his dalliance with their late mutual friend, the poet Evan Morgan, but after a while Huxley is reported to have found Falchi distasteful. At the time of Huxley’s death in November of 1963 (the same day JFK was assassinated), the great writer was probably at least glad to be ridding himself of the ex-priest who kept pestering him to collaborate on a literary translation of the Ramayana. Huxley went into the ether—his doors of perception were cleansed; he gazed upon the infinite; and Alessandro Falchi was no longer even a memory.

Aldous Huxley (1894 -1963). British author of Brave New World, Island, The Doors of Perception, and Heaven and Hell.

Falchi stuck around Los Angeles for a few more years, growing ever more indolent and dissolute. He became a fixture at the homosexual soirées hosted by Isherwood and Don Bachardy, and later began experimenting with psychedelic drugs. In 1965, while Pope Paul VI was presiding over the close of the Second Vatican Council in Rome, his future replacement had become quite enamored with LSD. Intemperate use of the lysergic would prove to severely hobble his mind; this, alongside the syphilis, ultimately sealed his fate. By the time he first put on his papal garments in 1972, he was a rather confused and empty-headed old man who often exhibited a blank, dead-eyed gaze. Just as ancient Rome had a deranged syphilitic sitting on the throne during the reign of the emperor Caligula, so too did modern Rome have one in the mid-1970s, seated on the chair of St. Peter in Vatican City. But Falchi had one thing going for him: he looked the part. The plastic surgery procedures had been going on incrementally for over four years. It was precisely his clueless state in life which had rendered him so compliant to his handlers. They had sculpted him very nearly to imposter perfection.

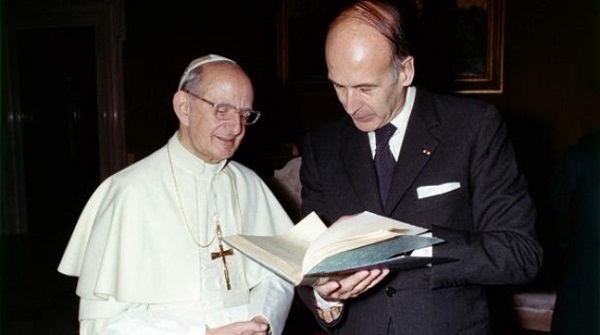

It was his behavior that began to raise hackles. He was passable when celebrating Mass or waving to crowds, or even making brief speeches and giving blessings. But people meeting him in private papal audiences were confounded by his bizarre non sequiturs, his uncomfortable silences, and his inability to make eye contact. Foreign dignitaries trying to discuss serious political situations were met with vapid responses. One of them was the President of France, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. A young journalist covering their meeting found himself appalled at the pope’s inability to say anything of substance. When the president asked him a detailed question about unrest in Lebanon, the supposed Pope Paul whispered the gnomic reply, “I have not found such faith in all of Israel.” When the President politely said he appreciated the bible reference but desired to talk about the Lebanese particulars, the pope cut him off. “It’s not just a reference,” he said softly. “I am Jesus the Christ. I am the Greatest I Am. As the Lord God said to Moses, ‘I AM THAT I AM.’” The journalist did not scruple to hide his amazement. At a press conference afterwards, he asked Giscard d’Estaing if he thought the man he met with was really the pope. (The president sighed and rolled his eyes, dismissing the question as “absurd”—but not without the hint of an amused smile at the suggestion.)

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing meeting with Alessandro Falchi in December 1975. The book is the Vatican library’s copy of a rare 1922 edition of the medieval French saga The Song of Roland, illustrated by the French artist Edmund Dulac. (“I shall never love you,” Roland cried, “for you are falsehood and evil pride.” Stanza CXXXI).

Other audiences passed in similar fashion. Most people attempted to put a charitable spin on it. The pope was getting old; it might be the onset of dementia. The pope was a busy man; his schedule has probably worn him out. The pope was having an “off day”; he hadn’t gotten enough sleep—meeting dozens of people at meeting after meeting was bound to make anyone confused. But for some people, the oddball behavior was too much to ignore. Monsignor Robert Flynn, an American priest from the Archdiocese of Newark, recalled personally meeting the pope twice: first during his papal visit to New York in 1965, and later, at the Vatican, in 1973. He did not mince words. “Something very diabolical is going on here,” he told a confrère during his trip to Rome. “There is no way that man is the same person I met with eight years ago. There is simply no way.” Uninvited ears might’ve been listening in, because Msgr. Flynn was the victim of several violent home invasions in his rectory during the remainder of his priestly career. In one of these incidents, an attacker broke both of his arms and four of his ribs with an aluminum baseball bat. Police informed him the assailant would face attempted murder charges if found (though he never was). On one hand, this might be expected: it was Newark, New Jersey. On the other hand, there is this: upon his retirement, Msgr. Flynn went into hiding.

Doubtless it was a “something is amiss with the pope” rumor similar to the ones mentioned above that Mrs. Lueken became privy to, and she inserted it into one of her fraudulent revelations. The fact remains that her full account was wrong. The pope had not been murdered. Either the story had gotten twisted and more elaborate as it travelled—as the original message gets garbled in the children’s game of “telephone”—or Mrs. Lueken added the murder as part of her own lurid whimsy. If she did, it was almost prescient, for the original plan, indeed, was to have the pope murdered. When he eluded the designs of his would-be assassins, they simply progressed to the next stage and proceeded with propping up his replacement double. The details of all this will be provided later, so as to keep things chronological. And with that, we can finally take our leave of Frau Lueken—a phony visionary, for sure, but nonetheless a recorded testimony to the imposter claim, and very early on. Let us call her Exhibit A.

Danke, Veronika.

Answering a frequent objection: the entropy wrought by Time

One of the most common (and tiresome) attempts to refute the idea that Pope Paul VI is still alive is to point out the simple fact of his birth in Anno Domini 1897. Often comes the eye-roll and the usual rejoinder: “but he’d be a hundred and nineteen years old!” Well, yes; he would. But lest such an advanced age be considered outside the realm of human possibility, it should be remembered that the oldest known documented person was a Provençal Frenchwoman named Jeanne Calment, who lived to be 122—a full three years older than the pope currently is. More recently, we have the fascinating claim of Mbah Gotho, an Indonesian peasant who attests to being well into his 140s. (Mr. Gotho’s documentation remains unsubstantiated, however, so the official distinction still belongs to Mme. Calment).

It’s not surprising that Mr. Gotho is from Indonesia, where a common dietary staple is the delicious fermented soy product known as tempeh. (Anyone who has ever had a spicy coconut-peanut-lemongrass tempeh curry, served over white rice, knows the gustatory and digestive delights of this miraculous Indonesian creation). Extreme longevity has not been uncommon in the Far East, where rice and soy are prevalent in the diet. There is also a commendable strain of taciturn stoicism running through traditional Asian culture; its people often age less obnoxiously than those who insist on “living life to the fullest!” or “making the most of the golden years.” Asians seem to burn the candle more conservatively. They don’t exhaust themselves on dining out or lavish cruises or the endless chatter of the self-important. We can picture a wiry and wizened old Chinese gentleman, keeping to his spartan room, sitting on his mat, low-key and contemplative, puffing on his pipe, rising only to get himself a bowl of rice or a cup of tea.

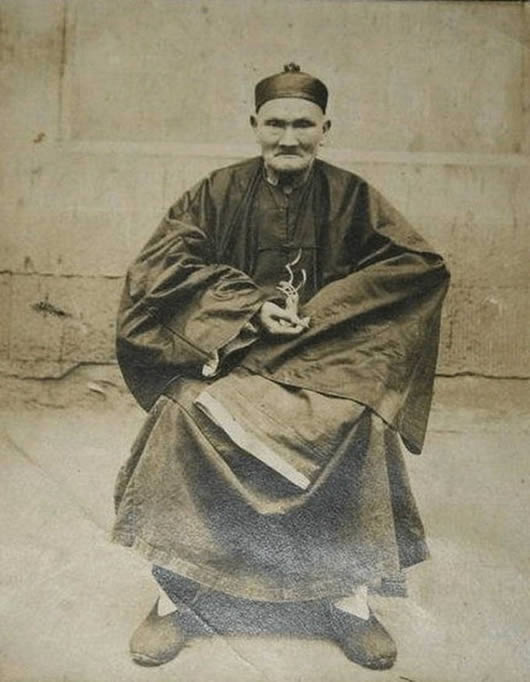

Li-Ching Yuen, alleged duocentenarian (c. 17th or 18th century – 1933)

We cannot easily imagine this of the elderly in the modern West. We would be more likely to think of puffy recliners, loud televisions, fattening foods, dyed hair, pastel nylon windbreakers, and irritable personalities. The modern mind is always restless, and forever unsatisfied. Sadly, the Western mentality has infected even Asia these days, and now most humans across the world have more or less forgotten the pleasures and benefits of a dignified quietude.

It may be relevant, then, to consider that Pope Paul’s present regimen in Portugal is conducive to good physical and mental health. He reportedly keeps to the earthy vegetarian diet of the medieval monastics: oat porridge, lentil soups, potato stews, dandelion-&-radish salads, and various root mashes; his evening meal is supplemented with a small portion of bread and cheese, along with a glass of wine. He has no TV or computer. His sedentary activities consist of reading and playing solitaire (or, when with company, whist). On Saturday afternoons he allows himself a single cigar. He takes a constitutional walk twice daily: in the morning, a brief stroll around the cloisters, and in the afternoon (weather permitting) a longer ramble in the countryside with his dog, an almond Abruzzo named Caetanus. The pope’s gait is painfully slow, of course, but what do you expect?—the man is six score years less one, for heaven’s sake. Caetanus himself is eighteen (slightly older than the pontiff, in dog years) and his master’s pace suits him just fine.

All of the above has been to answer the objection in purely secular terms. There are also religious precedents to take into consideration. Saint Servatius, known for his mystical vision of St. Peter, is estimated to have lived from some time in the first century until AD 384, making him at least nearly three hundred years old at the time of his death. And taking the bible into account, there are the obvious examples of the antediluvian Hebrew fathers who lived to astonishing ages. Adam, Methuselah, and Noah measured their lives in centuries, not decades. Is it not possible that the supernumerary years given to the patriarchs of old might be granted, in this strange and special age we live in, to the Patriarch of Rome?

Introduction

Once this blog has presented its research in full, it will hopefully be proven that the man named Jorge Mario Bergoglio, known to the world as “Pope Francis” is, in fact, not the pope. Nor were his three predecessors: Benedict XVI, John Paul II, and John Paul I. None of these men were the Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church. History will deem them heresiarchs, usurpers, and antipopes. And this is for the simple reason that Pope Paul VI never died.

Indeed, His Holiness still lives. He went into exile in 1972. At the Vatican, he was replaced by a double. The network of machinations behind this demonic act of subversion are manifold and intricate, ranging the whole gamut of the enemies of the Church—Freemasons, Kabbalists, occultists, Mohammedans, and others; in this blog they will all be exposed. God willing (if I am not killed before I can finish this endeavor), their work will be shown for the trickery it is, for it comes from the devil himself, “a liar and the father of lies.” One thing is for certain: the gates of hell shall never prevail against the Church. Soon the true and living pope, Sancte Pater Paulus Sextus, will once again step into the light of world—instaurare omnia in Christo (“to restore all things in Christ”).

For those who doubt, I ask only for your patience. Should you want to give it, the next post is here. Fiat lux!