Non-Catholic readers of this blog may have some confusion over the use of the term “modernist” since, in common parlance, modernism typically denotes a literary and artistic movement in the first half of the twentieth century, evoking things like the poetry of T.S. Eliot or the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. In Catholicism, however, modernism refers to a movement originating slightly earlier (in the late nineteenth century) and having to do with things like critical readings of the bible, or attempts to harmonize the faith with contemporary movements in philosophy and culture—to rid the Church of her reliance on antiquated dogmas, and to re-imagine the faith in purely modern terms. It was denounced as soon as it began. The most famous condemnation is Pascendi Dominici Gregis, an encyclical issued in 1907 by Pope St. Pius X. “We have witnessed,” he wrote, “a notable increase in the number of the enemies of the Cross, who, by arts entirely new and full of deceit, are striving to destroy the vital energy of the Church, and to utterly subvert the Kingdom of Christ.” He noted, too, that those who sought to destroy the Catholic Church were now doing their work from within: “the partisans of error are not only among the Church’s open enemies,” he observed, “but also—most dreaded and deplored—in her very bosom, and are all the more mischievous the less they keep in the open.”

Pascendi Dominici Gregis signaled the alarm and put up the bulwark; alas, it failed to deter the modernist beast. There were so many dissidents in the Church, of so many different stripes, that the movement became a hydra, a many-headed monster—if you chopped off one head, two more grew back in its place. In the end, the spiritual cancer of modernism metastasized, and nearly the entire hierarchy wound up being converted. A half a century after Pius X denounced it, most of the prelates in the Catholic Church were unrepentant modernists—including the subject of this blog: the then-Archbishop of Milan, Giovanni Battista Montini. When the Second Vatican Council opened in 1962, even the pope himself was a modernist: John XXIII said he wanted to “throw open the windows of the Church to the world and let the fresh air blow through.” Out with the old, in with the new. When the council closed, modernism was solemnly enshrined in its documents. Religious liberty, ecumenism, tolerance, and liturgical renewal were the order of the day. And meanwhile, Abp. Montini had been elevated to the papacy following the death of Pope John: he was Paul VI now. He gave an enthusiastic public speech at the close of the council, heralding “a unique moment: a moment of incomparable significance and riches.” No one gave Vatican II a greater endorsement than the pope who gift-wrapped it to the world.

So yes, Pope Paul VI was a modernist heretic. But understand this: it was only outwardly. It was not of his own free will. In truth, a terrible curse was upon him. Twenty-seven years before he became Pope Paul VI, Giovanni Battista Montini crossed paths with a dark and elemental evil. In time it overtook him; he was helpless but to become its pawn. Just as Satan “entered into Judas,” an unspeakable goetic malignancy had taken hold of Montini’s soul and oppressed him. Daily he was besieged by a throng of unrelenting demons, like the riot of devils in the many renderings of the Temptation of St. Anthony. So long as he did their bidding, they relented, and he was at ease. The moment he tried to defy them, however, they would assail him with gruesome horrors and unendurable physical anguish. In the following few posts I will explain. We will have to go back, initially, to the period (1916-1920) when Montini was in seminary, where he first encountered Alessandro Falchi; and then later to his time as a member of the Roman Curia in the 1930s, where he ultimately met the daemon that would possess him for three decades. We will have to examine some aspects of Edwardian occultism, as well as Italian communism and Freemasonry. But the objection will be answered: Pope Paul VI was under a terrible sway, one that he did not begin to emerge from until 1968, when he shocked the Vatican and the world by issuing his encyclical Humanae Vitae, a document that boldly reaffirmed the Church’s traditional stance on birth control. It was a surprising conservative about-face from the progressive gospel which had been proclaimed at the council. Virtually everyone had expected Paul VI would take a softer stance. And yet he did not. By 1972, the pope was free of his curse completely, and he publicly and defiantly proclaimed to an audience the unalloyed truth: “the smoke of Satan has entered into the Catholic Church.” He really did say that. You can look it up. And in doing so, he signed his own death warrant. Two months later, he was in exile.

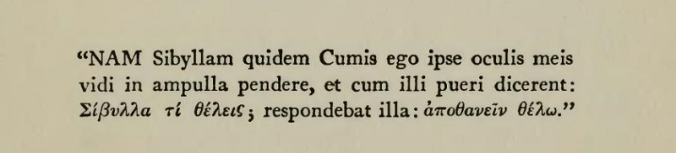

Epigraph to The Wasteland (1922). “And when the boys used to say to her, ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she replied, ‘I want to die.’”