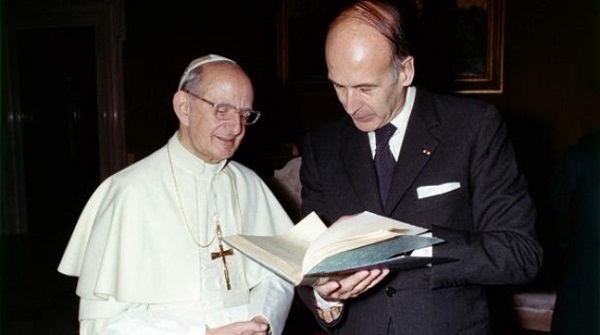

This blog has thus far been following two separate timelines: first, the chronicle supplied by Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua (which I have summarized up to his encounter with the occultist and papal chamberlain Evan Morgan in 1917), and second, that of Baltasar Fuentes Ramos (whose account has been provided up to the point of his meeting with Borges in 1966. I am attempting to persuade Señor Fuentes to permit me the publication of more chapters from his short story, The Wandering Jew, but he is currently incommunicado. He has told me he has no interest in reading this blog, so an appeal to him here would probably be futile). Today, then, will commence a third timeline, much belated but rather essential, concerning the very subject of this blog, Pope Paul VI.

Over the years following his conversations with Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua, my father undertook some research into the life of the current pope. (For newcomers to this blog, the current pope is Paul VI, and not the Argentine antipope calling himself Francis, who reigns with a liberal fist at Rome). My father’s notes from this endeavor are sufficient enough to provide a basic biographical sketch of Paul VI covering the period prior to his elevation to the papacy. Truth be told, this is not a terribly fascinating life to recount. He was more or less ordinary: a child of his mediocre era, born into a post-Risorgimento Italy, one where the ancient kingdoms and traditional politics had been supplanted by post-Enlightenment ideals, and one where influence of the Catholic Church and the old nobility were beginning to wane. (My father, always the cinephile, makes a passing reference in his notes to Luchino Visconti’s 1963 film The Leopard, which is about the painful transition in Sicily, from a mannered society of custom and virtue to a new order of egalitarianism and personal liberty. The title character is an aging aristocrat unable to adjust to the sweeping societal changes: he is a leopard who cannot change his spots).

Giovanni Battista Montini came of age long after this transition. He studied for the priesthood at a time when Scholastic theology was still being taught in the seminaries, but also when the ideas of modernism were pervasive enough for Pope Pius X to attempt a purge of its cancer from the among the clergy. He worked in the Roman Curia during a period when the Church was suffering from an existential identity crisis: whether to hide her light under a bushel and conform herself to the world, or to shine as a lone beacon of truth and tradition in a world gone mad. Before he lost his autonomy in 1935, Montini tended to be a fence-sitter in this crisis, but he usually erred on the side of caution. It will be shown that he was mostly a moderate. “Moderate” is almost a pejorative these days, but the man who would be pope was neither lukewarm nor unprincipled in his faith. He was simply able to see both sides of an issue. In this sense, he passed F. Scott Fitzgerald’s test for true intelligence: “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” Perhaps that sums him up best: ordinary and uninteresting in many respects, but with a keen intellectual curiosity, and a natural enough instinct toward conservatism to keep him prudent. Lastly, it might even be useful to consider his life in all its normalcy, as a tonic against the collective shrieks of invective and calumny that have been heaped upon him over the years: that he is a modernist heretic, a homosexual, a Freemason, and various other slanders. None of that is the truth about him. The truth is quite mundane.

CHILDHOOD

He was born on the 26th of September in 1897 into a family of upper-middle-class means, and was christened Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini. The father, Giorgio Montini, came from a respected Brescian line of doctors, lawyers, and writers. He made his living as the editor of a Catholic newspaper, Il Cittadino di Brescia. The mother, Giuditta Alghisi Montini, hailed from a notable and wealthy family, but her parents had died when she was young. Her guardian was the mayor of Brescia: a leftist and known Freemason named Giuseppe Bonardi. (It might be added that the teenaged Guiditta had, blessedly, spent most of her time away from this loathsome person, being schooled by French nuns in a convent in Milan). It is sometimes alleged that his mother’s family was Jewish, which would be interesting if true, but this appears to have no basis in fact. The Alghisi of his mother’s line were Catholic aristocrats of some antiquity, and were distantly related to the Renaissance architect Galasso Alghisi.

Throughout his youth, he went by the nickname Battista. He had an older brother named Lodovico (b. 1896) and younger brother named Francesco (b. 1900). From their mother, the boys learned French. They took their primary schooling from the Jesuits at the Collegio Cesare Arici, and played their sports at a boys’ club at the church of Santa Maria della Pace, administered by Oratorians. Two of the Oratorian priests there became mentors to Lodovico and Battista. Their names were Fr. Giulio Bevilacqua (no apparent relation to Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua) and Fr. Paolo Caresana.

Famiglia Montini, circa 1904. From left: Giorgio, Giovanni Battista, Guiditta, Lodovico, and Francesco.

The household was multi-generational: it included the boys’ paternal grandmother, Francesca Buffali Montini, and a spinster aunt, their father’s sister, Maria. Both women strove to infuse the children with a love of the Catholic faith, but Battista seems to have preferred adventure tales instead, particularly those with a nautical theme—“danger on the waves,” for some reason, appealed to the child. His favorite bible stories were Noah’s ark and Jonah in the belly of the whale. An illustrated compendium of sea monsters was a mainstay on his nightstand; his favorite leviathan was the giant Norse octopus known as the Kraken. He was an avid reader of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and much later in life, when he visited the United States in 1965, an interviewer asked his opinion on American culture. He confessed that he was not well-acquainted with it, but added that he owned an Italian translation of Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick, which he called “a magnificent story.” His personal assistant when he was the pope, Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua, remarked that Paul VI frequently used the nautical references to the papacy and the Church, such as “the fisherman’s chair” or “the barque of Peter.” (It might be presumptuous to read too much into a childhood fascination, but one wonders whether perhaps the boy, amidst his grandmother’s exhortations to piety and his storybook tales of the sea, was drawn subconsciously to the symbolic notion of the Catholic Church as the ark outside of which there is no salvation, being tossed about on the tempestuous ocean of sin, enmity, and worldliness. That would probably be too Jungian. In any case, he would one day become the boat’s captain).

In other respects, there was little to suggest his later becoming a priest. He enjoyed card games, particularly whist, which was the favorite of his brothers as well. Together they needed only a single friend or a willing adult to make the foursome required to play. When Battista was nine years old he told his aunt he wanted to become either a sailor or a writer. When he was eleven, he had eliminated the sailor option out of pragmatism, for lack of knowing how to swim. Becoming a writer was now his sole ambition; his interests were in poetry and, following after his father, journalism. His favorite sports were cycling and soccer—although doctors asked him to limit his participation in both of these activities in 1910, which is the year when he began to experience a chronic heart flutter. Added to this, he also came down with gastrointestinal troubles. This period would prove a significant turning point. The once normal and healthy youngster became an invalid.

ADOLESCENCE

Owing to his illnesses, he was pulled out of school for months at a time, and given his education by private tutors. He also began to stay, for reasons of convalescence, at the bucolic family villa in Verolavecchia, one of the ancestral homes of his mother’s family. He was typically accompanied by his Aunt Maria during these stays. For the heart issues, his doctors prescribed rest and relaxation; for the gastric problems, he was put on a diet of strictly cold foods, and advised to snack only on yogurt. He was allowed to take a walk once a day, which he sometimes took with his tutor, Durante, as well as the villa’s caretaker, an elderly man named Michele, and Michele’s two Irish wolfhounds.

Villa Montini, where Battista spent much of his adolescent and teenage years due to illness. Anyone who knew him from the period of 1910 to 1920 would probably have found it incredulous to think that the sickly boy would one day live to be a hundred and nineteen years old.

During one of his prolonged stays at Verolavecchia, he had a juvenile encounter with romance. A property adjacent to the Montini residence was being rented in 1910 by a Greek family named Xenakis, from the island of Spetses. On one of his afternoon walks, Battista (then twelve) met the Xenakis’ fourteen-year-old daughter Nina: she was seated calmly on a gravel path, stacking stones into a small cairn. On the day they met, he was traveling alone, with only Michele’s dogs for his company. Whatever conversation he had with Nina Xenakis is lost to history, but for him it must have been a magical encounter. My father’s notes contain a passage from Durante’s diary. Durante was twenty-one. Apparently Nina was smitten with the tutor and not the student. A pathetic love triangle ensued. Wrote Durante:

“There is nothing in my life more annoying at this time than the combined lunacy of these two children. Not even the infernal bird whose screeching wakes me up at night or startles me in the middle of the day. (I must find out what species of bird this is. Its call is the shrillest and most startling noise I have ever heard. Several times I have gone into the woods with Michele’s rifle, ready to stalk and shoot the creature as soon it starts up. But it never shrieks when I’m out there. Yet if I go back inside, not ten minutes later it returns to its noisemaking. I have read and re-read, several times now, Schopenhauer’s great essay On Noise. Commiserating with the German master through his sublimely cantankerous writing is my only consolation). The children are even worse than the bird, however. My student, who harbors aspirations to be a writer, composes overwrought love poems daily, which I am obliged to read and comment on. The object of his poetical delirium is a bookish Hellene, pudgy yet somewhat cute, with freckles covering the bridge of her nose, and crystal green eyes. But she is an impossible bore. She is wholly obsessed with the stone structures built by prehistoric peoples: dolmens, stone circles, and the great megalith on the Salisbury plain in England called Stonehenge. Her aspiration in life is to be an archaeologist and study these ancient phenomena—but, she tells me, she would be happy to give it all up if I were to make her a marriage proposal. Unfortunately, she has developed an affection for me. I find myself on the unwanted receiving end of a schoolgirl crush. Her Italian is very poor; the family is from some forgettable Greek isle, and the brazenness with which she flirts with me is almost as irritating as the unintelligibility of her speech. If I stay inside, I am in the company of the besotted boy and his wretched poetry. He imagines himself a Petrarch, and the dull Greek lass is his Laura. Yet if I venture outside, it is not long before the barefoot girl in the floral dress conveniently strays onto the villa grounds to make tedious and grammatically terrible conversation. And always—always—there is the bird.”

FORMATION

He earned highest honors when he took his exams at a state school in 1913, aged sixteen years old. He would spend the next three years preparing for his maturità classica, being tutored by Durante as well as a friend of his father’s, a retired professor named Labriola. During this period his health was improving, and he was living more often with his family in Brescia, and also spending time with his Oratorian priest friends, Fathers Bevilacqua and Caresana. At this point he seems to have begun discerning his call to the priesthood. An entry in Durante’s diary describes the tension in his reading habits. Montini was alternating between religious books (such as The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, and Introduction to the Devout Life by St. Francis de Sales) and the works of secular writers, such as the 19th century Italian poet Vittorio Alfieri and the 17th century Dutch philosopher Benedict Spinoza. Spinoza had been the recommendation of Durante, but Fr. Caresana disapproved of the selection. “Spinoza was deemed unacceptable by his spiritual director, due to his constant reliance on classical pagans instead of the Church’s great doctors and saints, as well as the fact that his books were on the Index, condemned for containing pantheism, and coming, no less, from an apostate Hebrew. Even the Jews had disowned him. So into the trash he went.” (It is unclear whether Durante was being literal or figurative when he says Spinoza went into the trash. It doesn’t seem in keeping with the young Montini’s character to throw books into the garbage. In any event, it would be Pope Paul VI himself, in 1966, who would formally abolish the Index Librorum Prohibitorum—though not, it must be noted, of his own volition. But more on that later).

His inclinations toward the priesthood did not diminish his desire to become a poet or journalist. With the outbreak of World War I, his Catholicism became infused with a youthful activism and political bent. He and a friend, Andrea Trebeschi, founded an independent periodical in 1914 entitled Numero Unico. Labriola oversaw and guided their efforts; Montini’s father allowed them the use of his newspaper presses for publication, and Fathers Bevilacqua and Caresana contributed short pieces. In the end, however, the journal received a poor reception and quickly folded. In 1915, Italy entered the war. Montini enlisted for military service, but (unsurprisingly) was turned down after failing his medical inspection. His brother Lodovico joined the 16th Artillery Regiment; Father Bevilacqua became a chaplain to the 5th Alpine Regiment. A year later, Montini had finalized his decision to become a priest, and in 1916 he formally enrolled at the Brescia Seminary, in a small class of little more than a dozen students, consisting mainly of young men whose physical disabilities rendered them unfit for service in the war, including Claudio Gagne-Bevilacqua with his shortened leg, and Alessandro Falchi with his poor eyesight. Durante wrote in his diary that when he finally parted with his pupil of nearly nine years, he shook his hand warmly, and told him how impressed he was with his “maturity, intelligence, poise, and good sense.” Apparently the boy who had once written desperate poetry for Nina Xenakis had grown into a thoughtful and serious young man.

While at seminary, he remained on his doctor’s orders to keep to a special diet and get plenty of rest, so he lived at home rather than on campus. Father Caresana supplemented his theological studies, and his friend Andrea Trebeschi continued to assist him in his writing endeavors. Together they would make a second attempt at a Catholic political journal. This one would prove more successful. It was called La Fionda (in English, “the Sling”—a reference to David’s weapon against Goliath), and it gained a respectable popularity, particularly among the membership of the Catholic Student Union, FUCI (Federazione Universitaria Cattolica Italiana), and one of its early supporters was Pier Giorgio Frassati, who seems to have been something like the Italian version of Dorothy Day. Montini articulated his politico-religious vision in La Fionda: that Europe in the midst of the war was a continent on a sure path to self-destruction unless it recovered its Christian roots. But he stopped well short of advocating for traditionalism; he argued for more of a return to the gospels than to the Church. His thinking was possibly influenced by Vladimir Solovyov, a Russian Orthodox writer, two of whose books Durante had gifted to Montini upon their parting (“I gave him a pair of books by Solovyov, telling him that if he would not have Spinoza or Schopenhauer, then this Russian mystic was the closest thing Christianity had to offer”). In any respect, he saw himself and his Fionda colleagues as taking on the establishment. In a typically tendentious editorial he declared, “no, we will not pay heed to the aging and irrelevant pedagogues, with their doctorate degrees and their empty bluster. We will instead make a fresh start with the Master, the Rabbi, Jesus Christ. Yes, a fresh start!—however difficult, and on our own, if needs be.” This reads like the idealism of the young, but it is fairly representative of Montini, as he had actually settled on a moderate course. He rejected on one hand the nihilism of the radical left as well as the rising fascism of Mussolini; but neither did he exhort a full-hearted return to the throne-&-altar scheme. He kept his Catholicism orthodox, but in his politics he was not exactly influenced by Joseph de Maistre or Chateaubriand. His political thinking during his years in seminary was mostly along the lines of the Sicilian cleric Don Luigi Sturzo, who founded the Italian People’s Party, based on the Catholic economic philosophy contained in Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, as well as a firm commitment to social reform. But it should be noted that in doctrinal matters, no liberalism crept into Montini’s thought. He wrote an article on the question of a reunion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox, and he made no ecumenical concessions. He cited Solovyov as well as St. Maximus the Confessor, and catalogued the many aspects of Orthodoxy which he admired, but in the final analysis he insisted that unfortunately no return of the schismatics to the bosom of Rome could be possible without their contrite capitulation on the filioque or papal infallibility.

Prior to taking his minor orders, he made a pilgrimage with some other students in 1919 to the Benedictine abbey at Monte Cassino. He wrote home to his grandmother and aunt: “I find this place an inspiration. It is the solemn and beating heart of a civilization which we must not allow to disappear. Rather its ideals must be rekindled, turning men’s minds to the things that are above, and restoring to the nation its Catholic culture, its ancient faith, its ora et labora.” His conservatism was beginning to shine through.

He took the cassock on the 21st of November of that year, and received the tonsure on November 30th. He became porter and lector on the 14th of December, and a subdeacon on the 28th of February in 1920. He completed his studies in the spring of that year. On Sunday, May 30th, in the church of Santa Maria belle Grazie, he celebrated his first Mass. He had been ordained a priest the previous day, in a class of only thirteen, due to the war’s depletion of seminarian ranks. It is probably the only noteworthy aspect of this otherwise mundane biography to mention that Alessandro Falchi was included in the remaining dozen. Lying prostrate on the floor of the church that Saturday afternoon were two men who would both eventually occupy the fisherman’s chair. One of them would be the last pope of the twentieth century: the last pope to celebrate the Tridentine Mass in St. Peter’s and the last pope to receive a coronation with the papal tiara. The other would be the first antipope of the modern era. Sic transit gloria mundi.