The following post is a portion of the story by Baltasar Fuentes Ramos called El Judío Errante (English: The Wandering Jew), which appeared in his school’s literary magazine, La Caligrafía, in December of 1965. This was the story mentioned in a previous post: it was the winner of a writing contest judged by Jorge Luis Borges. I do not yet have Fuentes’ permission to publish the story in full due to his reservations about the content; however, he has allowed for the publication of the first three chapters. It is reproduced here in a translation made by Polly Mendowe, who I would like to thank for her diligence. She appended a note to her translation which I will include as a preface:

“William—As requested, here is the story in English. Thank you for the generous payment. It’s a very strange tale. There was one particular word in the piece which gave me some difficulty, and that was the word escarcho. The literal translation would be “cockroach,” but the word is used in the context of an insult pertaining to the writer’s glasses, and I am unsure whether a literal rendering would be accurate. I assume it to be a colloquialism employed by some of the lower classes of Buenos Aires. “Bug eyes” was the closest thing I could surmise, but since the Spanish word for eyes (ojos) is absent, I’ve chosen to leave it untranslated.—P.M.”

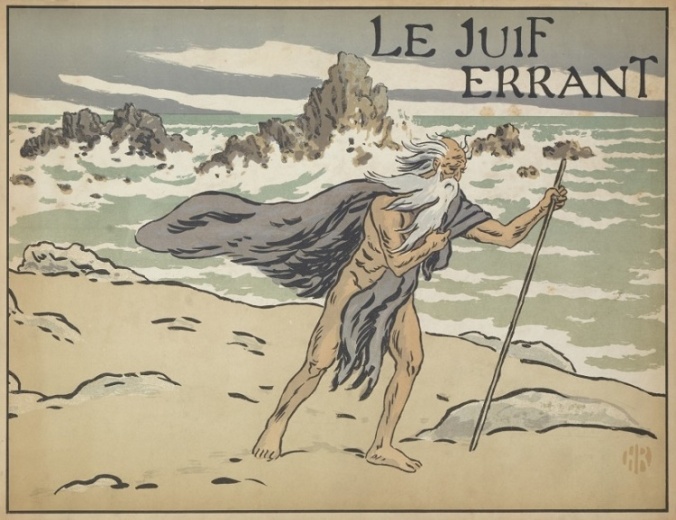

THE WANDERING JEW

1. A few brief facts about myself, who has met the person in the title.

My name is Baltasar Nicolas Fuentes Ramos. I am fifteen years of age, a loyal son of Argentina, and a devout Roman Catholic. My family is (in my opinion) a noble one. We draw our lineage from Spain and the Philippines. We derive our nobility not from grandiose titles or worldly riches, but rather from our dedicated obeisance to Holy Mother Church. Truly, our treasure is in heaven. My family is permeated by the Catholic religion, through and through! I do not even like using such a phrase as “the Catholic religion”—since, really, there is only one true God, one true Christ, and one true Church, and all other forms of worship and belief are either heretical movements or pagan cults. There is, therefore, in actuality, only one religion! There was a pope (whose name, I am ashamed to say, I cannot recall) who once said something to the effect that “only a Catholic is rightfully deserving of the honor of being called a true Christian.” I am kicking myself (well, not literally) right now because I forget the particular pope and the name of the document. I believe it was perhaps Pius IX or Pius X. I have a favorite uncle who is a learned priest. Normally in a situation like this, I would phone him up and ask him for the citation (he would know it off the top of his head, I’m sure), but I don’t want to disturb him as he prepares for the solemn season of Advent.

Because my family has an abiding love for Christ and His Church, many of my aunts and uncles are priests or religious. I have several aunts who are nuns (all of them belong to the order of the Poor Clares), and two uncles who are diocesan priests. There is, unfortunately, one uncle who is the black sheep of our family, and I am loathe to remember this man who has brought such disgrace upon both himself and my entire family by becoming a filthy schismatic, having joined the Greek (so-called “Orthodox”) sect, and who now lives as a monk (or, more accurately, as a long-bearded sadhu) in an abbey on Mt. Athos in Greece, no doubt sitting cross-legged and chanting some idiotic mantra in that Byzantine meditation practice called hesychasm. He is a smear on my family’s otherwise spotless record of devotion. He is a horrible traitor to the faith, and I pray often for his conversion, that he may return to the bosom of Rome before he dies, lest he surely suffer the eternal flames of hell. But I digress.

My favorite uncle is the Very Reverend Monsignor José María Fuentes, rector of the Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel in Recoleta, Buenos Aires. Every year I spend my summer vacation with him. For two whole months I get to assist him as an altar server and secretary. I consider it a sacred privilege to be so closely involved in all the functions of parish life, being at his side as he shepherds his flock. I always look forward to it. In fact, I am looking forward to it right now, just thinking about it!

2. My scuffle with cruel and ignorant hoodlums. How I came to best them, and caught my first glimpse of the person in the title.

It was in January of last year when these events transpired, on either the fourth or fifth day of the old octave of the Epiphany (I can’t remember exactly). I was in the rectory office, typing a letter for my uncle while he was reclining comfortably at his desk, enjoying a cigar and a glass of colheita port wine. He was being kind enough to take long sips and puffs during the pauses in his dictation, so that I might keep apace, as my typing skills are quite poor.

In the midst of this pleasant clerical work, the phone rang, and our domestic idyll was quickly ended: my uncle found himself dispatched to the deathbed of a former member of the parish. This man, whose name was Javier Ambrosio, had once lived in my uncle’s nice neighborhood of Recoleta, but he had fallen on hard times and ended up dwelling on the southeastern outskirts of the city, in the not-so-very-great neighborhood of Barracas. He remained loyal to my uncle, however. He abhorred the liberal and progressive movement in the Church (which, unfortunately, is spreading in our time like an epidemic. Plague of locusts!). He was especially not fond of his parish priest in Barracas, who felt emboldened by the liturgical experiments being recommended by the current Vatican Council, and was already daring to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in the vulgar tongue of Spanish instead of the sacred language of Latin! On his deathbed, Señor Ambrosio summoned my uncle for his last rites. He was quite sure his local priest was a filthy modernist heretic. (Requiescat in pace, Javier Ambrosio, thou good and faithful servant).

The day was hot. We took an olive green taxi to Barracas. Señor Ambrosio lived on the fifth floor of a tenement house. The walk up five flights of stairs was going to be a feat of endurance for my uncle, who is a man of considerable heft and girth. He knew that he would require refreshment and replenishment once he reached the top. “Be a good lad,” he instructed me, wiping his brow with his handkerchief, “and run down to the local shop. Fetch me some mineral water. And a wedge of Gouda cheese, a roll of pepperoni, and a stick of bread. Also, a bottle of Jameson.” He handed me a crumpled wad of bills.

While my uncle climbed the stairs, I went to the nearest corner store and purchased his supplies. (God bless the kind clerk of that store: he did not trouble me over my buying of whiskey). As I returned, however, I was accosted by a crowd of young toughs. I had noticed them loitering on the steps of the building when we first arrived. They must’ve overheard my uncle’s instructions, because it seems they wanted the whiskey I had in the bag. But first they wanted to harass me.

“Ai there, little escarcho,” sneered one of them, drawing attention to my eyeglasses. (I am horribly near-sighted). They were listening to a transistor radio. There was an irritating rock n’ roll song playing; the singer kept moaning about a “little red rooster.” (I swear, I cannot imagine a more brutish and barbaric form of music as rock n’ roll). One of these hoodlums (short and squat, and broad-shouldered with a scrunched-up face like a bulldog’s) twirled a tennis racket menacingly.

“Who was that priest?” another one asked. “Was he your father?” They all laughed in that high, keening sort of hooligan laughter that gives you a fright when you hear it.

Now I am not a person to suffer insults gladly, especially when the insults are directed at members of my own family, and particularly when they are meant to calumniate an obedient officer of the Lord such as my uncle. I didn’t care if these hoodlums were going to beat me up. I am the kind of person who will take a beating in defense of the honor of the Church. I have always admired the incredible fortitude of the martyrs, who sometimes went to their deaths with a smile. (One of my favorites is St. Lawrence, who mocked his captors even while they roasted him over an open flame. “Turn me over,” he told them—“I’m done on this side.”)

I gave these goons my bravest reply: “that excellent and holy priest,” I said, “is my uncle. I pity you for questioning his chastity, as you will surely burn in hell if you don’t repent. I pray that you will see the sinfulness of your ways.”

More laughter was roared in reply. One of them said, “what makes you so sure he’s chaste, escarcho? He clearly doesn’t care about the commandment against gluttony. I’ve never seen such a fatty!” Again they laughed.

All I could do was repeat myself. “I pity you,” I told them a second time. “I pray that you will come to see the sinfulness of your ways.”

Their ringleader cut to the chase. “Let’s stop this mucking about,” he said. “You’ve got a pint of Jameson. Now give it here.”

I pulled the bottle of whiskey from the bag. Without a word, I flung it down on the sidewalk where it promptly smashed. (If my uncle couldn’t have it, neither could they). Several of them jumped back in surprise, which soon turned to aggravation over having gotten the rolled-up hems of their stylish pants wet. Their jocular attitude was gone. Now they were angry.

Their first order of business was to rudely snatch my bag. Soon they were snacking on my uncle’s victuals. Next they menaced me. “Pick any one of us,” said their leader. “That’ll be the one you fight. You see? We’re fair. One on one.”

“I challenge you instead to a game of chess,” I told him. One of them chuckled but none of them laughed. The leader stared me down, wordlessly. “Very well,” I said. “If it must be a physical contest, how about squash?” I gestured to the bulldog-faced thug with the tennis racket.

“You want to play Ronni in squash?” he snorted, and leaned in close to my face. I could smell the pepperoni he was chewing on his breath. “Sure. That works out, escarcho. That raises the stakes. If Ronni here wins, you get the whooping of your life. And if you win, then we’ll just let you go, scot-free.”

Wordlessly, Ronni got up and slipped inside the building and, a minute later, came out carrying a second racket, dressed in a tank top and Bermuda shorts. It was then I realized this “Ronni” was actually a girl.

The hoodlums led me across the street and down an empty alleyway. I was pushed along from behind by Ronni, who kept prodding me in the back with her racket. We crossed an abandoned railway yard, full of disused train cars, sitting on rusty tracks and baking in the sun. We ducked into another, thinner alley running in between two empty brick factory buildings, hollow and crumbling, with broken windows. Soon we were in a tight brick maze of alleyways, turning left, then right, then left again, and I was lost beyond all hope. Decades-old trash littered the gravel beneath our feet. Graffiti and ugly folk murals covered the walls.

Eventually, we went through an archway and arrived in a broad courtyard abutted on three sides by tall, decrepit fin-de-siècle houses. A dead tree stood in the center of this courtyard, surrounded by a crumbling stone fountain, drained and dried, full of coarse weeds and dead leaves.

The fourth wall of the courtyard was a high brick wall, the back of a huge factory building. It was painted with an old advertisement for cigarettes; the paint was peeling and sun-bleached, but the ad could be discerned beneath the aging. It was hawking an American cigarette brand called Lucky Strike. It read, “to keep a slender figure, no one can deny,” followed by the logo: “LUCKY STRIKE.” Beneath that was a picture of a lascivious young woman, dressed immodestly in a swimsuit and lying on a beach. In the corner of the ad was a packet of the cigarettes, along with a motto: “it’s toasted!”

Apparently we were to play our game of squash against this wall. Ronni tossed me one of the rackets. The other hoodlums retreated to the steps of the houses to sit down and spectate. Ronni then removed a tennis ball from her shorts pocket, and took the liberty of serving first. We had a brief volley which I won. I then served.

I am underweight, and not exactly strong. But I have the natural agility of the lithe and light; squash is a game that I excel at. Tennis also. I have always loved the racquet sports. After my first two serves against Ronni (neither of which she was able to return), I realized, to my great relief, that I was probably going to win. By my fifth consecutive uncontested point, I was sure of it. Even the impure advertisement didn’t bother me. In a moment of hubris, I looked at the cigarette motto and decided it applied equally to Ronni. “Ronni,” I thought to myself, “you’re toasted!” I may’ve even forgotten myself in that moment, and smiled. In retrospect, I should not have allowed myself to dominate. I should’ve deliberately lost points, and kept things close, and made it out to be the life-and-death contest it was supposed to be, so that my captors would think I had eked out my freedom by my sweat and my tears and every last heroic effort in my bones.

I did not, unfortunately, do that. After my seventh straight easy point, the game was (prematurely) over. Ronni’s bulldog face turned to me, snarling with rage. She threw her racket at me with incredible force; it struck me in the nose. Blood splattered onto my glasses. I saw stars and went down. I heard the scuttering sound of many feet, moving swiftly from the steps across the courtyard dirt. The next thing I knew, a hail of kicks and blows rained down upon my body. I curled up and prepared to die, praying the Hail Mary silently in my head.

At one point, I opened my eyes. I had thought the entire gang was beset upon me, but apparently they were just gathered around in a circle as spectators. Ronni, it seemed, was doing the battering. I turned my head from her angry face and flurry of fists; it was then that I saw a figure standing under the archway. It was an old man, I noticed. A solitary old man: rather tall, vaguely handsome in the distinguished manner of the aged, with long silver hair pulled back behind his ears. His face was cleanly shaven, and not even very wrinkled, but there was an aura of something unspeakably ancient about him. It would be difficult to reckon, going by the basic indicators, that he was too many years over seventy. But at the same time he seemed more elderly than the most wizened and withered person in an old folks’ home.

He was a curious specimen; so engrossed was I with the oddity of his presence that I nearly forgot my pain and my praying. What also shocked me was the obvious nonchalance with which he watched my beating. He simply watched. He betrayed no emotion at all: neither pity for me nor enthusiasm for my punisher. Unlike the hoodlums, who were cheering Ronni on, the man watched my humiliation with complete neutrality. I have never seen (nor do I expect I shall ever see again!) a more stoic visage. As captivated as I was, I was brought back to my pain by a fist smacking my right eye. Shortly after, I lost consciousness.

3. In which I meet with the person in the title, and he makes a peculiar claim about himself.

The world was a blur when I woke up: my eyesight is extremely poor without the help of my glasses, and I was missing them. I got up onto all fours and felt around for them. Finding them, I was crestfallen: they had been stepped on. Both lenses were broken, and the frames were hopelessly twisted. I folded them up as best I could and slipped them into my shirt pocket. I stood up and dusted myself off. I could make out a figure sitting on the steps where the hoodlums had perched: it was the tall, silver-haired old man. He appeared to be calmly eating the remaining half of my uncle’s baguette.

I was incensed at the fact that he had witnessed my beating and done nothing to stop it. Since he was not making any attempt to converse, I confronted him with my ire. “Why didn’t you help me?” I asked.

“Help you how?” His voice was gently accented; he sounded vaguely aristocratic.

“By stopping those kids from attacking me.”

“It was only one of them who was attacking you. And that was a girl.” He held out the baguette for my taking. “Would you like some bread?”

I spat on the ground and refused the bread. “You’re a disgrace,” I told him frankly. I proudly straightened out the crucifix which I wear around my neck. If he was a Christian, I intended to remind him of his deficiency. “You’re like the priest and the Levite in the story of the Good Samaritan,” I said.

The old man was unfazed. “The priest and the Levite came upon the traveler after he was beaten,” he said. “Well, here I am. You have been beaten—and I’m not just walking on by and leaving you for dead.”

“You’re missing the point. The point of the story is to help your neighbor.”

“Am I not helping you? I offered you some bread. Look, there’s some mineral water here, too.”

“I know there is. I bought that bread and that water myself. Give it to me.”

“Of course,” he said, handing it over.

I took a greedy bite from the baguette, and washed it down with a long swig of the water. Wiping my mouth, I lectured the man again. “The time to help me was when I was being attacked! But all you did was watch.”

The man betrayed no shame. Instead he pointed to my crucifix. “All He did was watch, too. Why do you suppose He didn’t smite those kids with a sudden crippling nausea, or strike them with lightning?”

“I don’t care for your tone of impiety,” I said. “Do you mock Christ?”

“Mock Him?” he asked. “Certainly not.” He smiled a wan smile. “I am the only person alive who has known Him.” (Normally I would’ve taken such a claim to be the ranting of some Pentecostal heretic speaking about his “personal relationship” with Our Lord, or the babble of some unhinged lunatic. But there was something about this person which prevented me from concluding that. He seemed to be claiming it as a straightforward historical fact.) “Indeed,” he continued, “I may be the only person on earth who adequately fears Him.”