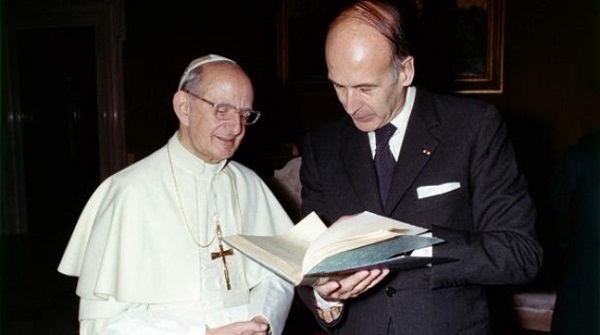

We come now to an important episode in the early history of Giovanni Battista Montini. In January of 1923 he returned to his apartments in Rome to await his appointment to the Vatican Secretariat. While he waited, he occupied his time with a light regimen of studies at the Pontifical Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics, and with composing some wishy-washy political pieces for the student newspaper he had founded back in Brescia, La Fionda. This period of limbo lasted for five months: from January until his appointment to the papal nuncio in Warsaw, Poland in June. On the surface, it may seem an inconsequential stretch of time in the life of the young priest. But on the contrary: there was a significant incident. It occurred in early May, when King George V and Queen Mary of England made a state visit to Rome as the guests of Victor Emmanuel III, the penultimate King of Italy.

Archival footage. (This video has no sound).

The visit lasted for five days and was known as “English Week” by the Italian public, who welcomed the royal couple warmly. Arriving along with the king and queen was an unofficial contingent of various English Royalists as well as English Catholics, including the papal chamberlain Evan Morgan, the 2nd Viscount Tredegar. (Any readers unfamiliar with this demented personage are advised to kindly acquaint themselves with the short biography which was posted earlier on the blog).

On Thursday of that week, Father Montini was invited by his physician and friend Roberto Zorza to attend a dinner at the Roman residence of Prince Francesco Massimo, a prominent member of the so-called “Black Nobility”—those among the Italian aristocracy who continued to remain loyal to the Church, and who were appalled by both the fascist and people’s movements. Father Montini was able to feel vaguely sympathetic to the Black Nobility. Typical of him, his politics at the time were riddled with uncertainty and fence-sitting. His brother Lodovico was a staunch opponent of the ascendant fascism of Mussolini’s party, and his father was a supporter of Don Luigi Sturzo’s Italian People’s Party (in Italian, Partito Popolare Italiano, or PPI). But Montini had been in heady discussions of political theory with his friend Zorza, a monarchist of some conviction. Montini was never quite converted to the monarchist stance himself, though he was coming to appreciate it: God alone was the source and font of morality, and if the Church was removed from the political equation, then morality would descend into the hands of the populace—and this would mean morality by the consensus of the mob. One of his essays in La Fionda was critical of a rabble-rousing speech Sturzo had given at a PPI convention in April of that year. Montini did not mention monarchism as an alternative, but he did wonder whether Sturzo’s uncompromising advocacy of popular sovereignty would be favorable to the Church in an increasingly secularized era.

At the dinner, Montini and Zorza shared a table with several members of the English delegation. Among them was a dapper twenty-four year old named Hollander Zea, a British national of Peruvian descent who had been disowned by his family at age nineteen after a public conviction for homosexuality. He was supported financially by a wealthy great-aunt in Peru, and moved with ease among the more dissolute circles of the English aristocracy. Eventually his path had crossed with Evan Morgan’s, and they became friends until Morgan’s death in 1949. Zea was not, however, a participant in Morgan’s occult activities. He was an avowed atheist, and considered the existence of the devil as unlikely as the existence of God, and in his diaries he expresses an ongoing befuddlement with Morgan’s religious pursuits. In one passage he described attending one of Morgan’s Luciferian rituals in Paris, remarking: “a man of Evan’s intelligence has no excuse for indulging in this nonsense, but I confess I find this sort of lunacy amusing. Do they really think they will conjure the devil with candles and runes and backwards Latin? I could barely suppress my laughter when the old woman started shrieking.” (The “old woman” mentioned in this passage is Myriam MacKellar, since he uses the name “Myriam” interchangeably with “old woman” in many of his entries). Zea was a prolific diarist, believing his own life to be of the utmost importance, and he chronicled his thoughts and misadventures in great detail. His journal entry is the only known record of the events at Prince Massimo’s palace that particular Thursday.

EVENING OF 10 MAY

The prince’s mansion. In a vast dining room, beneath crystal chandeliers, and among tall potted ferns. We were seated with a middle-aged insurance clerk from Surrey named Jerome Fitzgerald, who was tall, solemn, and horse-faced. In the course of Fitzgerald’s conversation with Evan it became clear that he was devout in his Catholicism. At one point he began speaking of the several scapulars he wore underneath his shirt. We were then joined by a pair of Italians, a young Roman doctor with his hair prematurely graying, surname of Zorzo, and a gentle, big-eared priest from Milan whom Zorzo introduced as Don Battista. (Montini was from Brescia, obviously, but he had recently finished his canon law studies in Milan, which was probably the cause of Zea’s misunderstanding here. “Don Battista” was possibly an instance of Zorza making a good-natured reference to Montini’s recent admission to the Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics, as by all accounts he preferred to be called simply “Father Montini.” And “Zorzo” was obviously misheard.—WJQSM). The priest’s English was abysmal, whereas Dr Zorzo’s was quite good. The doctor became a translator for the priest after a most fascinating argument ensued.

Fitzgerald expressed a desire to attend on Sunday the beatification ceremony of the famous Jesuit Cardinal, Robert Bellarmine. Fitzgerald said that in his opinion, Bellarmine was the most important figure of the sixteenth century. The doctor then commented, saying he had been given his Christian name after Bellarmine (“Roberto Bellarmino,” as he put it in his euphonious Italian). Fitzgerald declared Bellarmine to have been more important to the Catholic Church than Pius V or Leo X or Charles Borromeo, even though a crucial part of Bellarmine’s legacy had been obscured and defamed. “And what part was this?” asked the priest.

“His defense of the scriptural doctrine of geocentrism,” said Fitzgerald, and suddenly the debate was on. The priest was visibly taken aback by this, but then he chuckled and shook his head in dismay. “No, no, no,” he chided, “Bellarmino was wrong on that. In fact, we must admit the Church was wrong.”

The whole table was then treated to a history lesson on the Galileo controversy. I confess to being surprised by Fitzgerald’s position. I was unaware there were Catholics in existence who still clung to the ridiculous view that the sun revolves around the earth. But he defended himself with eloquence and erudition. In fact, I fear he bested the poor young priest.

The priest’s first line of defense was to say that Bellarmine had made a simple mistake in judgement. He had failed to realize that the geocentric passages in the bible were supposed to be taken figuratively, not literally. Fitzgerald replied: “but it was not just Cardinal Bellarmine who concluded this. The Early Church Fathers unanimously believed in and taught a geocentric cosmos. Were they mistaken also?”

Don Battista said that the Fathers were simply innocent of the science. They accepted the Ptolemaic model like everyone else did at the time, as the astronomy to prove it incorrect did not yet exist. Fitzgerald countered: “they were not taking their beliefs from Ptolemy. They were taking them from Holy Writ.”

The priest softly smiled. “A common misunderstanding. I know the passage. We studied this in seminary. The Psalmist says, ‘the Earth will not be moved.’ But this only means that the Earth will not be moved from its course. If you have studied Hebrew, you will recognize that the mowt of the niphal stem in that passage means that nothing will deter the earth on its orbit. It does not indicate geocentrism.”

“I have not studied Hebrew myself,” Fitzgerald conceded, “but with all due politeness I must defer to the Jewish philosopher Maimonides over your own study of Hebrew. Surely a learned Jewish scholar is a greater authority on the Hebrew language than a Catholic priest? Maimonides studied the Hebrew bible extensively, and he contended that the bible described the sun as revolving around the earth. I will assume that he, an eminent Jew, did not make a bald-faced error in basic Hebrew grammar. Unless, perhaps, biblical Hebrew is your particular area of expertise?”

Don Battista at this point was beginning to show signs of wearying. He was no longer chuckling and smiling so much. His adversary was giving him a harder fight than he expected. He sighed. “What we must conclude from the geocentric descriptions in the bible is that God, in speaking to mankind, was speaking to them in terms they would be familiar with. It appeared to the naked eye as if the sun was rotating around the earth. No one had telescopes in those days. So the bible was simply communicating in a manner which the people of the time could understand.”

“But the ancient Hebrews accepted the bible as the holy word of God. If it is true that the earth revolves around the sun, then why would he confirm his chosen people in a scientific error? I should also remind you that God’s revelation is for all people in all times. It is truly timeless! Why would God, in all his omnipotence, tailor scripture especially to the ancient Hebrews if he knew that it would be found troubling to people in the sixteenth century with telescopes?” Fitzgerald’s voice was rising. It was evident that he believed in this very passionately. “Cardinal Bellarmine’s brilliance was to recognize that all the scientists in the world, with all their telescopes, were nothing other than mere mortal humans with fallible instruments. The only assurance of truth we have is that which has been revealed from on high. If inerrant scripture is at odds with human science, then the science must be wrong. It is a heresy to claim that scripture contains any error. That is why Galileo and Copernicus were condemned. Geocentrism was a heresy and remains a heresy still. Heresy is heresy. Error can never become orthodoxy!”

The doctor named Zorzo was becoming exasperated in translating between the priest and his interlocutor. Don Battista tried to keep his response minimal. “The Holy Office that condemned Galileo was not infallible,” he said. “When they pronounced geocentrism a heresy, they were unfortunately wrong.”

“It was not just the Holy Office, however,” countered Fitzgerald. “It was Pope Alexander VII, who solemnly invoked Apostolic Authority in his bull Speculatores Domus Israel when he placed the heliocentric books on the Index and condemned them as heretical. So think of it. We have the geocentric descriptions in Holy Writ, the unanimous consensus of the Early Church Fathers, the condemnation of heliocentrism by the Holy Office, and finally the ratification of the Holy Office’s decision by the pope, in a formal decree which is binding on the faithful. Nothing could be more Catholic, as we have scripture, tradition, and the magisterium, all teaching in unison! How can anything buttressed by all three pillars of the Catholic Church possibly be overturned?”

At this point everyone at the table felt sorry for the poor priest, who was clearly being trounced. The doctor translated Fitzgerald’s screed to him softly, robbing it of its thunder. But the content remained. The priest speared a scallop in lemon sauce with his fork and moved it around on his plate. He gave Fitzgerald a kindly look. “I am afraid we will have to agree to disagree,” he said.

“Very well,” Fitzgerald told him. “But take caution, Father. If you accept the notion that the Church can overturn a solemn condemnation, you set a dangerous precedent. You make it possible for anything and everything to be overturned at some point in the future.”

Whoever Jerome Fitzgerald was, he is lost to history. A little-known insurance clerk from Surrey: a devout Catholic who followed his Anglican king and queen to Rome, possibly in the hopes that they might somehow convert to Catholicism, and the English throne be rightfully restored to the Church. One can only surmise about him. He is not mentioned again in Hollander Zea’s diary. But he seems to have been something of a prophet (for truly, “anything and everything” was overturned in the future, at Vatican II). The table was joined next by a pair of late arrivals, an Italian socialite and her son. The conversation then turned to gossip of no importance. Zea’s entry has no more relevance to the history of Paul VI until later on that night, when it recounts a conversation between Zea, Morgan, and Myriam MacKellar, while they were sitting on one of the palace verandas drinking white wine after most of the guests had gone home.

Evan’s thoughts turned to the young priest who had discussed the movements of the sun and the earth with the bachelor named Fitzgerald. He remarked, “I know of a priest who bears an eerie resemblance to that Don Battista at our table,” and Myriam nodded her head in agreement.

But I wanted to know if Evan believed in geocentrism. “What about you?” I asked him. “Do you believe that the earth is the center of the universe?”

“Yes,” he said, “as surely as I believe that hell is located in the center of the earth. As a matter of fact, this priest I know is the disciple of an exquisite demon who was once anciently worshiped as a Mesopotamian god, and whose cult migrated to India. Hell is real. It is populated with devils and the damned.”

I informed him for the hundredth time that I did not believe in any of this. He said to me, “whether or not you believe it makes no difference. It is still very real. Catholic and Satanist eschatology are very much in agreement. The final stage of history is upon us. Did you know, Christ has agreed to give the devil one hundred years to see if he can bring utter destruction to the Catholic Church? It’s quite true. Pope Leo XIII had a vision of this while he was offering Mass. It is now as it was in the Book of Job, Hollander, when the devil bragged that he could cause the most devout believer lose his faith.”

At this point the old woman chimed in. She stopped puffing on her long-stemmed cigarette long enough to say, “there is an intricate numerology surrounding this. We are working to unravel it.”

“Yes,” Evan agreed. “And we believe that I myself have a role to play. Did you know that I was born exactly nine months and nine days after Pope Leo had his vision? The number nine in Kabbalistic gematria has a profound significance, and two consecutive nines, such as nine months and nine days, are even more auspicious. Myriam and I have been in contact with many messenger demons, and there is an indication that I have a certain destiny in this scheme.”

I was too tired to listen to any more of their thaumaturgical ramblings. I dislike Evan whenever he gets in his religious moods, and I have always the old woman irritating from the day I was first introduced to her. I excused myself from the balcony, left the mansion, and returned to my lodgings, where here I presently sit, writing this. So ends another day.